Published: 11/24/2020

Dr. Seema Yasmin is shaking up the status quo in science and health communication, deploying and studying strategies for effectively conveying information to the underserved communities most impacted by medical misinformation.

By Lucas Oliver Oswald.

Interviewing Dr. Seema Yasmin about health communication is a bit like explaining epidemiology to Anthony Fauci – you are well aware she could do a much better job.

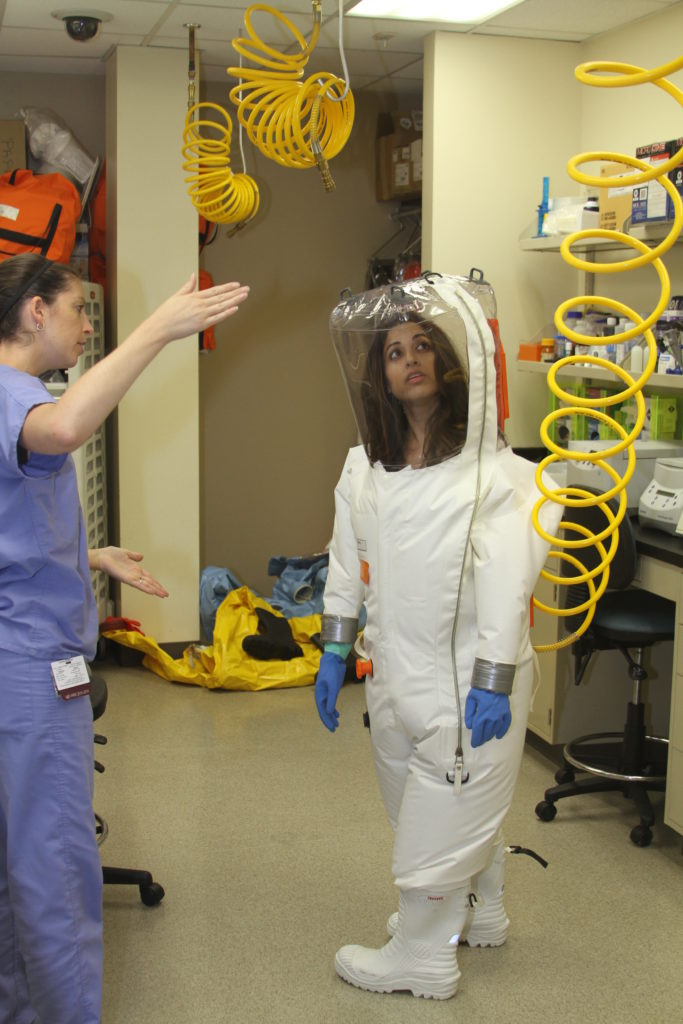

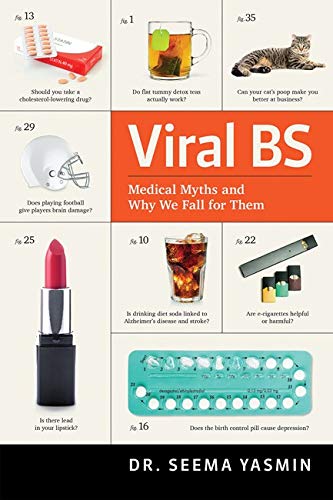

While all of her work in some way touches on communicating health to the public or specific audiences, she takes many diverse approaches to the goal. In addition to being an Emmy-award winning journalist known for her reporting on Ebola and Zika, she is also a former officer in the Epidemic Intelligence Service at the CDC, as well as poet, fiction writer, and author of 3 non-fiction books, one of which is set to be released in January, Viral BS: Medical Myths and Why We Fall For Them.

Considering these accolades, her writing across genres, and her ongoing research, the unifying thread in Dr. Yasmin’s work might be less so communication and more so empathy. Through many means, Dr. Yasmin seeks to understand her audience so that she can better inform them, arming them with the knowledge and understanding they need to protect themselves from the world’s many health threats.

I recently caught up with Dr. Yasmin to hear about her many approaches to communicating global health issues to audiences around the world.

1

Your research varies quite a bit in scope, from studying one-to-one interactions to global information trends. How do you do describe your research?

I have two primary areas of research: the micro and macro of health and science communication.

The micro looks at one-on-one conversations that might happen between a scientist and a member of the public, or a patient and their healthcare provider. We try to identify effective modes of communication and undo common outdated practices.

The macro of what we look at is the health and science information ecosystem — spread of misinformation and disinformation. Where you might have a disease outbreak that’s spreading, you often have a concurrent infodemic or a mis-infodemic.

We think those micro and macro areas are very much connected. Say someone walks into their doctor’s office and is thinking about the flu vaccine, but they’ve heard erroneously that if you get the flu shot, you could get the flu from the vaccine. They’re coming in with this wealth of information and misinformation. How is it that in an eight-minute consult, a healthcare provider is going to counter those falsehoods and those beliefs? So we look at that whole information ecosystem and what kind of strategic interactions can succeed within it.

2

You train clinicians to communicate with people that hold anti-science and anti-vaccination beliefs. What is wrong with the way we communicate and how do you try to correct that?

scientists and medical professionals have some pretty flawed means of communication.

For example, when the World Health Organization responds to an outbreak of measles in Eastern Europe by disseminating pamphlets, that doesn’t work. Dry facts bullet-pointed in a pamphlet does very little to counter the viral YouTube video of an emotional mother convincing you that her two-year-old got an MMR shot and then stopped being able to string together a sentence. A lot of what we do is undoing those existing, ineffective strategies.

Most science and health professions are not given communications training, and if they are it’s often boring, or worse, ineffective. We try to move people away from communicating strategies they are used to like teaching and lecturing and closer to listening and building emotional connections first. We do this by using tools from theater and improv training to increase fluency in non-verbal communication, observation skills, and to build confidence in spontaneity.

3

How does someone’s information ecosystem affect their behavior?

The goal is to understand how your health is impacted if you live in a place where you don’t have access to credible information.

In medical terms, if you live in a health desert, that means you have to travel more than 60 miles to get access to primary care. But there are also news deserts — places in the US where local news has been decimated. When a county loses its local newspaper, government salaries increase, taxes are hiked, and the county is considered a more risky investment and bond and loan agreements are not as attractive. But what is the impact on our health? With local news having disappeared in more than 1,300 U.S. communities, that means fewer people doing local accountability journalism, no hard-headed city hall reporter that sits in on all of the six-hour-long meetings to find out where your tax money is really going.

We already know that Black and brown Americans disproportionately reside in medical deserts. We know less about who lives in news deserts. So one project I’ve been working on is an interactive map that shows the coexistence of medical deserts and news deserts to help understand the health and health information needs of communities across the U.S. We can then understand how our health is impacted by the presence of absence of local news. It’s really bridging my dual training in epidemiology and journalism.

4

You’ve said your upcoming book uses a personal approach to understanding misinformation. Can you tell us about it’s origins?

I used to write a newspaper column called Debunked that answered people’s medical questions about things like vaccine safety, chemtrails, genetically modified food, and those sorts of things. My new book, Viral BS: Medical Myths and Why We Fall for Them, answers commonly asked questions and dissects medical myths to understand why they spread and why we believe what we believe.

Viral BS begins with me talking about my childhood and how I used to believe in conspiracy theories. I talk about the cultural context that allowed these beliefs to persist and the events that enable distrust in the medical and scientific establishment.

5

How can we do better as health professionals and health communicators to build trust?

Medical science has been built in a way that stokes distrust, on a backbone of unethical experimentation and exploitation of enslaved Black people, poor people, queer people, and people with disabilities. The scientific community mostly is not representative of the populations that we are purportedly supposed to serve so there’s a huge disconnect.

If the information that we wield as our rationale for being experts is entrenched in unethical experimentation and exploitation of vulnerable and marginalized people, then you have to talk about that history and atone for that past. I see very little of that in science and medicine. We’re starting to see it in journalism with news organizations such as the L.A. Times and National Geographic apologizing for their role in upholding white supremacy, but I haven’t seen that acknowledgment and atonement happen in science, and we need it.