Published: 06/10/2021

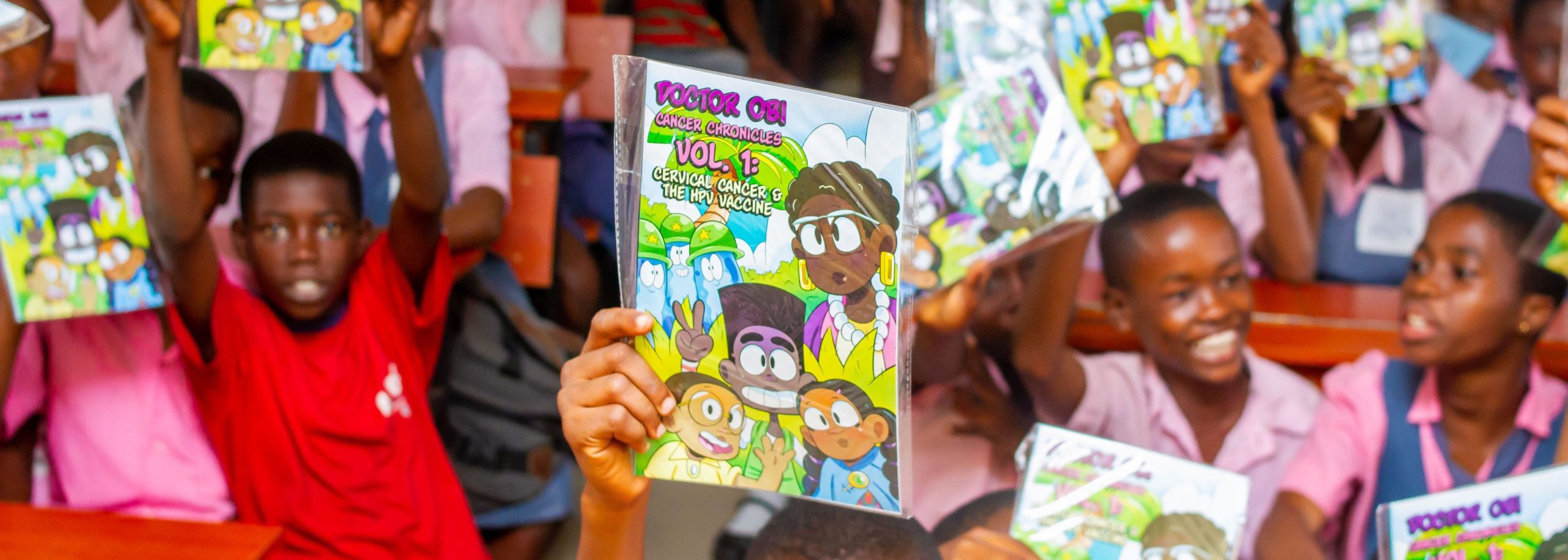

Above: Children at a junior secondary school in Lagos, Nigeria each received a copy of the Global Oncology “Cancer chronicles” comic book during a school educational assembly organized by CHAI, Global Oncology and CEAFON (Cancer Education & Advocacy Foundation Of Nigeria).

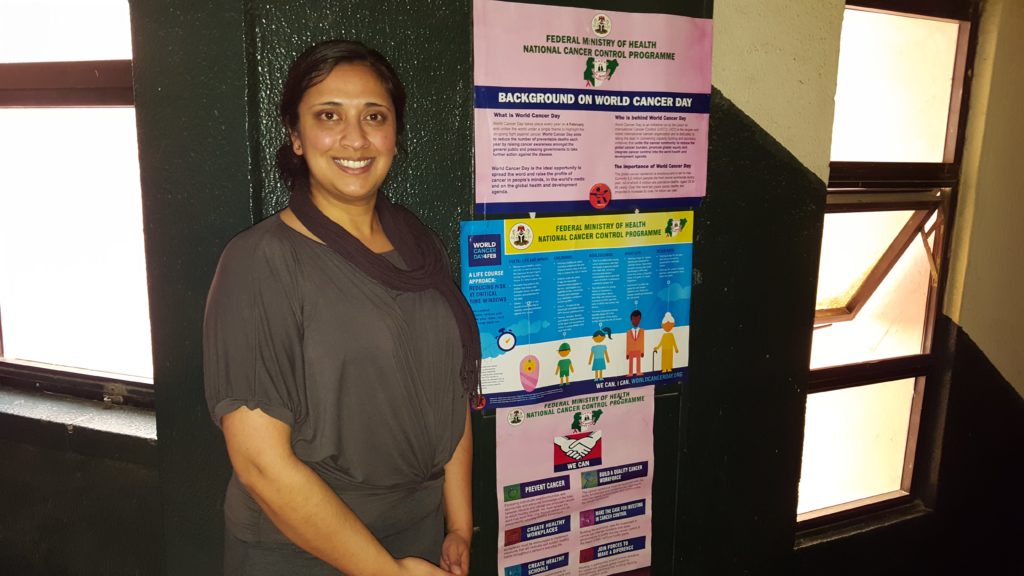

Through her NGO Global Oncology, Global Health Faculty Fellow Dr. Ami Bhatt is fighting cancer in places it has been historically ignored. Starting with a national campaign against preventable cervical cancer in Nigeria, she is on a mission to bring recent cancer advancements to every corner of the globe.

By Lucas Oliver Oswald.

In the United States, cervical cancer was once one of the most common causes of cancer death for women. In the past three decades, cervical cancer rates have been dropping steadily thanks to Pap smears and more recently the introduction of the HPV vaccine in 2006, which prevents the virus that is responsible for most cervical cancers. These simple preventative measures however have failed to reach most of the world.

Dr. Ami Bhatt believes that a simple preventative measure is within reach for low- and middle-income countries around the world. The HPV vaccine, which is now commonplace in high-income countries around the world, has the potential to end countless unnecessary cervical cancer deaths. That a set of injections can save lives is neither novel nor innovative, and yet there are enormous barriers to accessing this vaccine around the world. Today, Dr. Bhatt is starting a global campaign for equitable HPV vaccine access in Nigeria, where it stands to have an enormous impact. In her eyes, the campaign is long overdue — she has been seeing the impacts of inequitable access to simple cervical cancer prevention since early on in her career.

While doing her hematology and oncology fellowship at the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center, Dr. Bhatt was treating a patient from East Africa for acute lymphoblastic leukemia, an extremely aggressive cancer of the blood. He was lucky, and while undergoing intensive chemotherapy, a treatment he likely would never have been able to receive in his home country, he began to show signs of recovery. During this time however, his wife, who had been by his side throughout the treatment, began presenting symptoms of cancer herself.

In the United States, we are lucky to have regular cervical cancer monitoring built into our healthcare systems through regular Pap smears. Thanks to this early detection method, it is nearly unheard of to encounter a patient presenting with late-stage cervical cancer. When her patient’s wife presented with exactly that, late-stage cervical cancer, Dr. Bhatt was shocked.

“She was so late stage. She had never had Pap smears earlier on in her life,” Dr. Bhatt said. “That would almost never happen if she was born and raised in the United States. It was solely due to her being raised in a country where screening and HPV vaccines weren’t the norm.”

Shortly after her husband recovered, the woman died, a devastating loss that Dr. Bhatt knew to be entirely preventable.

“To have a patient die like that feels like a failure, it feels like an unnecessary death. I think it was that moment that crystallized for me the opportunity that we had, and also highlighted the vast inequity that exists across the world.”

Not long after, Dr. Bhatt founded Global Oncology with her colleague Dr. Franklin Huang, an organization devoted to ending unnecessary cancer deaths through known treatments and interventions around the world.

The fraction of global health funding that goes to cervical cancer is miniscule. This is largely because of an overwhelming stigma that cancer is extremely difficult to prevent and treat, requiring capacity and capital that is simply unavailable in most low-and-middle-income (LMIC) countries. There is truth to this — cancer treatment can be prohibitively costly — but lumped into this stigma is an array of low-hanging fruit in cancer prevention that is both easily implemented and much needed.

Though cancers can often arise randomly, public health campaigns can play a large part in preventing them from arising or progressing. The obvious example is anti-smoking campaigns, which have already saved millions of lives and stand to save many more, but many cancers are actually driven by infection.

“Many people don’t realize that 15% of cancers worldwide are driven by infections, and HPV is one of them,” said Dr. Bhatt, “and in LMICs we think that number is closer to 30% of cancer.”

Through Global Oncology, Dr. Bhatt hopes to implement these preventative measures in countries around the world. By taking advantage of the low-hanging fruit in cancer prevention that is already commonplace in high-income countries, LMICs can prevent millions of cancer related deaths without having to scale up treatment capacity.

Today, much of Global Oncology’s efforts are focused on Nigeria, a country with an already large population — the largest in Africa — that is rapidly growing.

Because of this extreme growth, Nigeria has an abundance of young people, specifically young women at the ideal age to receive the HPV vaccine, and because it is largely viewed as a leader for how the rest of West Africa moves in the health arena. Today, approximately 11,000 women die in Nigeria every year from cervical cancer. If Global Oncology is successful in their health campaigns there, that number could be reduced by 95%.

Deploying a vaccine to a country of 210 million starts with making the vaccine available, but it ends with educating the public on the importance of being vaccinated. Global Oncology has been taking on both prongs.

Working between the Nigerian global health partners such as the Ministry of Health, Global Alliance Vaccine Initiative, the Legislative Initiative for Sustainable Development, the Clinton Health Access Initiative, and vaccine providers like Merck, Global Oncology is hoping to make steps in increasing availability. They have worked hard to reinitiate stalled conversations on vaccine pricing and overcoming barriers related to vaccine distribution and uptake. If these continuing conversations go well, the vaccine might soon be available beyond just private providers.

Luckily the Nigerian government has been an ally in this to the extent that they are able, having identified cervical cancer as a priority area in 2015. Human welfare aside, ending cervical cancer also poses a large economic opportunity for Nigeria.

When a woman dies of cervical cancer, it is a prolonged and expensive affair.

“Families hemorrhage money, often going bankrupt, and the patient still dies,” said Dr. Bhatt. “And because these are often larger families, children end up growing up without a mother in a bankrupt household. These kids, sometimes referred to as ‘cancer orphans’, often drop out of school and the result is essentially the economic collapse of families. It has an enormous ripple effect and is very economically costly.”

With the vaccine access conversation underway with the appropriate stakeholders, much of Global Oncology’s work is now focused on communicating the need to be vaccinated to the public. Their approach has been multi-pronged, from a comic book targeting young girls to recruiting influencer advocates who voice their support on public radio and television.

The ambassadors they have amassed since launching the Nigerian campaign in 2018 is impressive. Many of these ambassadors have wide reaching influence to a range of audiences. One of them, Toun Okewale Sonaiya, runs the largest women’s focused radio network. Others, like Abimbola Ogunbanjo, the president of National Council of the Nigerian Stock Exchange have wide reaching business influence. These powerful influencers will soon be joined by a prominent new ambassador: former President of Nigeria Olusegun Obasanjo.

“With President Obasanjo joining, our audience for this message will be hugely expanded,” said Dr. Bhatt. “Not only can we reach more young women, but it will also have the domino effect of bringing on direly needed supporters and resources that can help us move from the planning and advocacy to the action phase. Given the severely limited funding available for global cancer efforts like this one, we can only succeed with the support of impact-driven philanthropic, corporate, and foundation partners.”

Dr. Bhatt’s work in Nigeria has a long way to go, but their progress in the last two years has been substantial. The challenges in low-income settings can be enormous. Global Oncology has carried out educational campaigns in 12 schools in two provinces, reaching at least 5000 children. However, in a country where around 50% of eligible girls are not in school, the ordinary route of a school-based educational campaign does not reach their entire target audience. Acknowledging this, they’ve begun discussions amongst stakeholders on how to execute a national campaign to reach beyond schools.

Still, with the work in Nigeria well under way, Dr. Bhatt’s goal remains larger.

Global Oncology has taken on much more than just cervical cancer in Nigeria. In the past 10 years they have tackled oncology efforts around the world. One of their first major accomplishments was helping to facilitate improved drug pricing for a much-needed cancer therapy in Botswana, and in 2020, they supported the opening of the first medical oncology clinic in Belize.

But the low-hanging fruit of cancer treatment and prevention can sometimes be more nuanced than vaccinations and drug pricing.

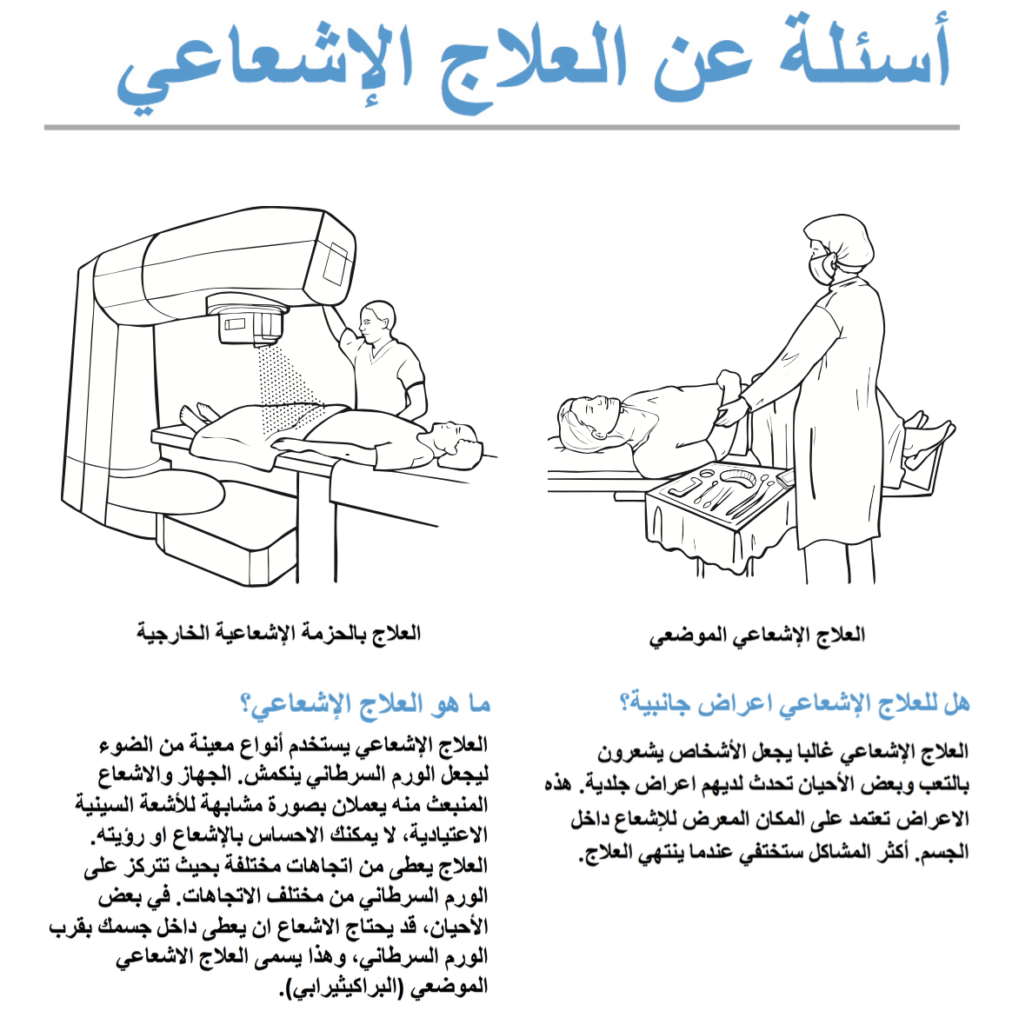

One of their longstanding initiatives has been a global educational campaign around treatment abandonment during chemotherapy. Early on, Global Oncology identified that in the low-resource settings where chemotherapy and radiation treatment was available, full recovery was still lacking because people tended to abandon their therapies when the extreme side effects took hold. In response they created low literacy cancer education materials that help patients understand what to expect when they get treatment and how to prepare for those side effects. They have since been translated into 20 languages and distributed in countries around the world.

While this work is ongoing, the Nigeria campaign is still Dr. Bhatt’s main focus at Global Oncology, with some big steps and announcements due in the near future. Despite the enormity of the challenge however, for Dr. Bhatt, Nigeria is just one piece in the larger puzzle.

“This campaign is not just the Cervical Cancer-Free Nigeria campaign, it’s just the cervical cancer free campaign,” she said. “In my lifetime, I have a very simple goal. By the time I die, which I hope isn’t very soon, I just don’t want there to be people who die of cervical cancer. We should be able to achieve that for cervical cancer in my lifetime.”