Published: 05/19/2023

New WHO resources underscore the life-saving value of kangaroo mother care and provide a roadmap for making it available to mothers and babies around the world.

By Jamie Hansen, Global Health Communications Manager

When Punita of Uttar Pradesh, India, learned she was having twins, her joy turned to worry after complications forced her to deliver prematurely. She experienced something common to many mothers of sick and premature babies around the world: Her infants were taken away and placed in incubators. For their first week, they were fed powdered milk rather than breastmilk as doctors sought to stabilize them.*

Punita and her family returned home a week later with enormous debt, anxious for the health of their babies, who weighed about three pounds each. A few days later, the twins began having trouble breathing and the family rushed them to a local hospital.

In stark contrast to their previous experience, Punita and her family entered a comfortable room full of other mothers and babies at the District Women and Child Hospital in Budaun, Uttar Pradesh. There, they learned about kangaroo mother care (KMC), which involves providing prolonged skin-to-skin contact and breastmilk to infants. With the help of her mother-in-law, Punita fed and held her babies close for nearly 18 hours a day. By the third day, the twins had gained nearly two-thirds of a pound and returned home, where they continued to gain weight and thrive.

Kangaroo mother care is a miracle. It gave our babies a second chance at life.

Punita, mother of twins

“KMC is a miracle,” said Punita. “It gave our babies a second chance at life.”

A life-saving strategy few have access to

More than a miracle, kangaroo mother care is a proven strategy that can prevent up to 40 percent of low-weight newborn deaths in hospitals. Immediate KMC after birth has been found to increase an infant’s chance of survival by 25 percent. Making KMC part of routine care for small or sick newborns can prevent half of preterm baby deaths by 2025, a Lancet study estimates.

“KMC is not just a strategy for low-resource settings,” said Gary Darmstadt, MD, associate dean for maternal and child health and professor of neonatal and developmental medicine in the Stanford Department of Pediatrics. “Current evidence tells us it is actually superior to current high-tech strategies.”

Based on this evidence, The World Health Organization’s Every Newborn Action Plan set a goal of universal KMC coverage by 2030. Yet, achieving these goals has proven difficult: In most countries, the availability of KMC services is still limited to a few central hospitals, where much of the population cannot access it.

Kangaroo mother care is not just for low-resource settings. Current evidence tells us it is actually superior to current high-tech strategies.

Gary Darmstadt, MD

To address this issue, the World Health Organization on May 16 released a position paper and implementation strategy to enable the expansion of KMC around the world. They follow a recent landmark publication recommending KMC as the standard of care for pre-term and low-birthweight babies. Darmstadt co-chaired these initiatives.

The guidelines recommend a dramatic shift in newborn care, one which prioritizes the mothers, newborns, and families as an inseparable unit at the center of newborn care — similar to Punita’s experience.

“KMC repositions power in the care of the infant, giving mothers and families a leading role,” Darmstadt said.

In Uttar Pradesh, a model for expanding KMC

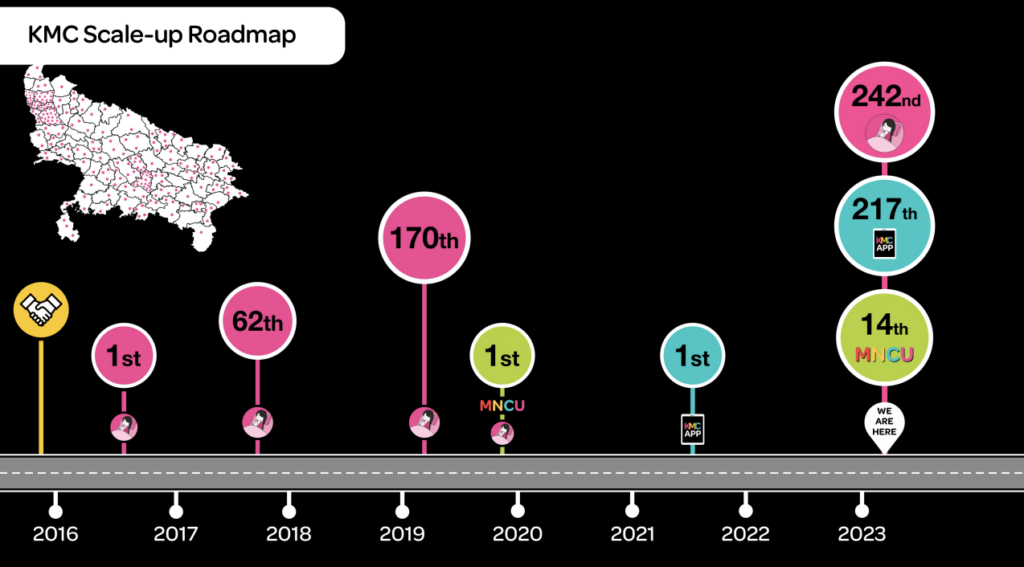

Punita’s state of Uttar Pradesh, where one in four newborn deaths in India occurs, offers a model for how countries can expand kangaroo mother care across a large region, even when resources are scarce, said Dr. Vishwajeet Kumar of Community Empowerment Lab. He helped develop a model for implementing KMC across Uttar Pradesh.

Kumar became interested in kangaroo mother care more than two decades ago, while seeking ways to prevent newborn deaths, especially in poorer settings that lacked high-tech equipment.

“We knew that every mother, irrespective of where she is from, would do everything possible to save her baby’s life,” Kumar said. “So one of the first questions we began to ask was, how can we empower her to do better?”

Dr. Vishwajeet Kumar

“We knew that every mother, irrespective of where she is from, would do everything possible to save her baby’s life. So one of the first questions we began to ask was, how can we empower her to do better?”

Kumar’s team began to explore interventions, including KMC, in the rural community of Shivgarh in Uttar Pradesh. They were amazed to see the number of deaths in premature infants drop by half in 16 months. Custom and local beliefs traditionally separated the mother and baby after birth, contributing to high rates of hypothermia in babies and low rates of breastfeeding, Kumar said.

“Kangaroo mother care actually helped them bring the baby where it’s best suited,” said Kumar. “When you bring babies into that ecological niche, they receive everything they need: love, food, warmth, and protection.” The benefits were immediately evident to mothers and families, he said. For instance, with the help of a thermometer, mothers holding their infant close to their skin could watch their temperature rise.

“Once we had the evidence, the government was very keen to scale this up in the community,” Kumar said. In India and beyond, mounting evidence led global leaders to recognize the life-saving potential of KMC. In 2014, 190 nations committed to the Every Newborn Action Plan to ensure that 90 percent of babies in their population have access to kangaroo mother care by 2030. And yet, these commitments and policies were not translating to widespread changes in care.

“We had a policy-level commitment to expand KMC coverage, but we didn’t know how to do it,” Kumar said of India. He was brought on to create a model to bridge the gap between research and policy.

Empowering families

Working in Uttar Pradesh, Kumar and his team identified key obstacles. The first was supporting the mother in providing KMC.

“The mother of a sick newborn may be exhausted or in need of emotional support, and yet we’re asking her to provide around-the-clock care. We needed to focus on creating an enabling environment for the mother,” he said.

We needed to focus on creating an enabling environment for the mother.

Dr. Vishwajeet Kumar

They designed KMC lounges where families remain together while receiving support and education.

For Punita’s family, the lounge was critical to providing them with the morale and support necessary for them to help their babies, Shivansh and Ansh, first survive, and then thrive. Punita’s mother-in-law described the lounge’s atmosphere as “like a family. “Everyone supported each other,” she recalled.

Uttar Pradesh now has more than 350 such lounges.

Finding nurses to be powerful champions of KMC, they provided training and support to help them fill this role. They also developed systems for immediately weighing and referring low-weight babies to KMC lounges.

Through this approach, and with strong support from the government of Uttar Pradesh, Kumar’s team showed how to expand KMC over a large region so that almost all infants in need received it. In one of the largest scale-ups of this mode of care in the world, more than 300,000 babies have now received KMC in Uttar Pradesh.

Expanding KMC globally

The lessons learned in Uttar Pradesh illustrate what WHO’s new recommendations are calling for. These recommendations emphasize structural changes to prioritize mothers and infants, political commitment, dedicated budgeting, and a system for tracking progress.

This is expected to yield enormous benefits of improved survival, health, wellbeing, and long-term human capital.

Gary Darmstadt, MD

The implementation strategy and position paper are aimed to inspire a renewed vision for transformed health systems, as seen in Uttar Pradesh, Darmstadt said. The vision, he said, is one “where mothers and infants are cared for together from birth, and parents and families have a central role in the care of their infants, thus humanizing health care.” He added, “This is expected to yield enormous benefits of improved survival, health, wellbeing, and long-term human capital.”

Read more in the implementation strategy and global position paper.

—————

*Punita’s story was told to CIGH through the Community Empowerment Lab. The cover image of the Kangaroo Mother Care Lounge in Budaun, Uttar Pradesh, India, was shared courtesy of the Community Empowerment Lab.