Published: 04/18/2022

A partnership between Stanford and an Indian network of palliative care centers has sparked a nationwide improvement system that is enhancing care for cancer survivors and inspiring similar projects across the globe.

By Jamie Hansen

Several years ago, Dr. Vidya Viswanath was overseeing a new palliative care team serving cancer patients at Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital Visakhapatnam – a unit of Tata Memorial Hospital , Mumbai and one of India’s busiest government-run cancer centers. Here, she saw the need to improve their systems to meet the overwhelming demand and improve the continuity of care to patients as long as they lived. In particular, their small but committed home-based care program, which was essential to easing suffering in those too sick or poor to travel, delivered inconsistent and often random service based more often on the availability of staff than the needs of patients.

“We worked with quantity,” she recalls. “And when you work with quantity, what often suffers is quality.” Her team struggled to respond to the care needs of the ever-increasing number of patients . “We were just triaging suffering,” she said. Viswanath knew there must be ways to provide more consistent care—but lacked the tools to diagnose the root causes of the problem.

Then, in 2017, an opportunity arose to participate in a quality improvement project in partnership with Stanford palliative care and improvement science experts. Quality improvement is an approach used to understand and address systemic challenges in order to measurably improve health care access and quality.

“We were a small but growing team, interested in improving, so when the National Cancer Grid-India invited us to participate in a quality improvement project we could incorporate into our daily work, we were eager to participate” she said.

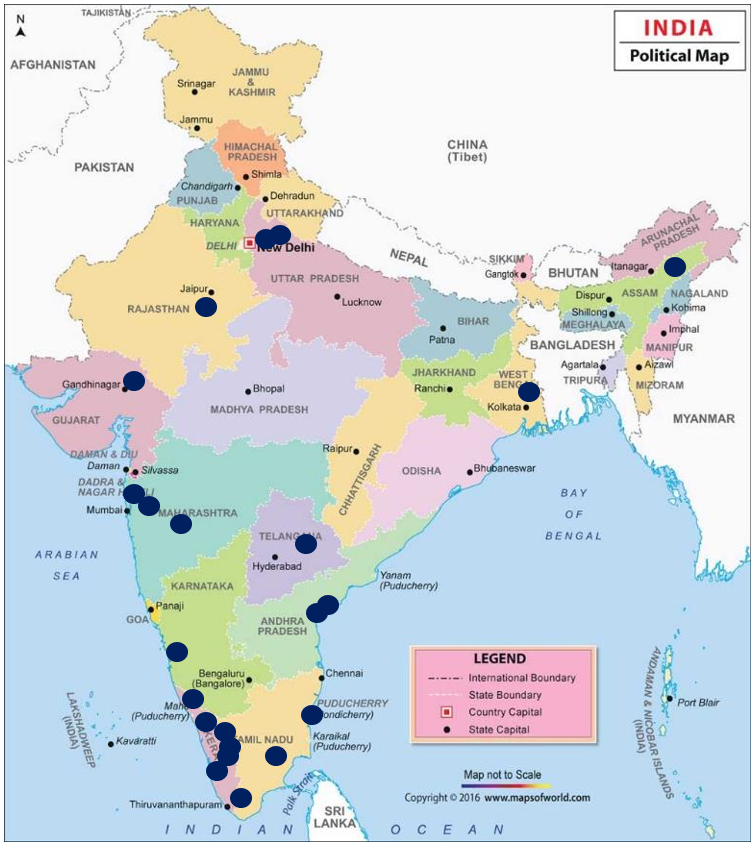

“We worked with quantity, and when you work with quantity, what suffers is quality. We were just triaging suffering.”

Dr. Vidya Viswanath

Viswanath and her team found an opportunity to study and solve their dilemma when they became part of a unique collaboration that forged lasting partnerships between Stanford and a network of institutions associated with the National Cancer Grid (NCG-India). This collaboration helped develop a generation of Indian quality improvement leaders and launched a country-wide improvement system that would come to be called EQuIP India. This system has now enhanced care for tens of thousands of Indian cancer patients. Stanford quality improvement leaders affiliated with the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health, inspired by this model, are now carrying it forward into other low-and-middle-income countries eager to improve the quality of patient care.

Improving End-of-Life-Care

The collaboration began at a 2017 palliative care conference in India, when Indian health care leaders seeking out information on improvement science connected with Stanford physician and professor Dr. Karl Lorenz.

Lorenz, as a leader of the VA’s national Hospice and Palliative Care Program and director of the operational palliative care Quality Improvement Resource Center, is an eloquent advocate for and internationally recognized leader in delivering quality health care that eases pain and helps individuals die with peace and dignity. While the approach of improving the quality of healthcare systems might seem abstract, Lorenz brings home what many practitioners find to be the sacred and life-changing power of the work.

“We’re uniquely skilled as humans at ignoring the tolling of the bell and its relevance to us,” observed Lorenz, who is also a Global Health Faculty Fellow at Stanford. “And yet we all experience suffering and loss — it’s one of the fundamentals of the human experience. Palliative care is about helping people acknowledge that tolling of the bell, and life’s finitude, and how they want to travel that path while they’re still alive.”

“Palliative care is about helping people acknowledge that tolling of the bell, and life’s finitude, and how they want to travel that path while they’re still alive.”

Dr. Karl Lorenz

In 2017, Lorenz had been invited to the palliative care conference in India to present about the framework and methodology of improvement science. Dr. Nandini Vallath, a national leader in palliative care in India, listened to his presentation and saw a light bulb flash: She realized Lorenz was describing the framework she and her colleagues had been seeking.

“I thought it made a lot of sense to build out our capacity to use the quality improvement methodologies he described,” she said, adding that many centers in India had begun to develop an interest in quality improvement, but lacked the experience and training. “I pursued Karl when he went out of the auditorium and asked, ‘How can we make this happen?’”

A Collaborative Approach

Lorenz responded with interest, and in the months that followed, the two developed, alongside colleagues from Stanford and India, a six-month, cohort-based training and mentorship program that paired teams from seven Indian palliative care centers with mentors from leading universities in the US and Australia. Lorenz worked closely with Michelle DeNatale, a global health faculty fellow and continuous improvement expert and Executive Director of Operations in Stanford Health Care’s Office of the CMO, to design the program. Soon, Global Health Faculty Fellow Jake Mickelsen, who had been leading improvement trainings at Stanford’s School of Medicine for nearly four years, joined the effort. They called the initiative Promoting Access and Improvement of the Cancer Experience, or PAICE.

Each team identified a problem they were currently facing in their clinics and, in close partnership with their mentors, used a quality improvement framework to address it – with remarkable results.

Mickelsen believes the program’s success was due, at least in part, to its project-based learning approach to tackling real-world problems. “You can go to lots of places and listen to lectures or watch videos about improvement science,” he said, “but we believe you learn best by doing.”

Mentorship played another critical role, he said. “In improving a healthcare delivery system, it’s nice to offer a method or approach, but it’s also helpful to have mentors who know the clinical subject matter and can share what’s being done in other places.” The mentorship and learning went both ways, he added: “Whether it be virtual or in person, meeting with the teams from India is a memorable learning experience. It’s stunning to look at the creative and innovative ways they find to offer care.”

Back at Homi Bhabha Cancer Hospital, Viswanath and her team worked with Mickelsen to apply the tools of improvement science to the often-hurried choices they regularly faced.

“When we multitask, we skip steps,” Viswanath said. “I’d think, ‘I have 40 patients right now, so I’ll do this, this, and this at the same time in order to get it done faster.’ Quality Improvement (QI) didn’t allow us to do that. It taught us to take one step back and think about where we wanted to go before moving forward. That was the beauty of QI for us.”

“[Quality Improvement] taught us to take one step back and think about where we wanted to go before moving forward. That was the beauty of QI for us.”

Dr. Vidya Viswanath

Taking that step back and using quality improvement tools like baseline analysis, key driver diagrams, and sustain plans, Viswanath and her team were able to identify and address the root causes of the inefficiencies, such as communications and cultural breakdowns. For instance, they realized that their medical social workers, nurses and IT staff, along with an NGO partner agency, could play a critical role in developing a more streamlined process for identifying the patients who needed assistance.

They developed a simple but sophisticated digital system for mapping patients and prioritizing them according to need. Using this system, the team expanded its capacity from 3-4 home visits a week to 8 visits a week by the project’s end. They’ve continued improving since then, and have leveraged a grant to support home visits through a project called “Integrated Hospital based Continuity of Care.” These visits are especially important to patients with debilitating illnesses like cervical cancer who receive vital services to lessen their pain and ease their transition towards end of life.

Viswanath recalled one young patient who benefitted from these more regular and coordinated services. The young girl could not walk due to amputation from her illness, but she was a beautiful painter, Viswanath remembered. She lived with her parents in a small home near the factory where her parents work.

“She benefited greatly from our ability to provide home care, as the parents could continue to work and earn their living and the child was able to get the best medical attention possible,” she said. One day, the girl and her parents stopped at the hospital on their way to visit their extended family at their family home in a faraway village. “With her charming smile, the young girl told me that she wanted to meet me and say goodbye – she had insisted. I got her some orange and apple flavored packaged Oral Rehydrating Solutions from the pharmacy and waved her goodbye,” Viswanath remembered. The girl died 10 days later. “This girl went through so much but the smile never left her face. We were privileged to look after her as an outpatient during and after disease-directed therapy through home-based care.”

Such system-wide improvements, with their tangible benefits for patients, were not unique to Homi Bhabha. Another center reduced the delay in palliative care referrals for cancer patients from 50 days to 14. Other centers saw staff efficiency increase, and in-clinic processes become more reliable and safer. And for many of the Indian participants, the program lit a spark that transformed them from students into mentors and quality improvement leaders.

From a Seed of Mentorship, a Forest Grows

“Toward the end of the program, I realized that I didn’t want it to end,” said Vallath, who in her first improvement project had learned from the dedicated mentorship of Stanford’s Dr. Stephanie Harman and Sri Seshadri. “The mentors were so patient and their approach so systematic. The way they engaged and responded to the questions of our team, at every step of the project made me deeply interested in the science behind it all…. and I wanted to build that very capacity within India.”

Vallath sought out and received a generous grant from Tata Trusts – India, a highly respected philanthropic foundation based in India, to fund the capacity-building for quality improvement in India. Alumni from several EQuIP cohorts continue to volunteer their time and efforts as QI Board members and mentors. The program operates as part of the Indian National Cancer Grid’s Quality Improvement hub, with Vallath leading it. It is called “EQuIP India,” meaning “Enable Quality, Improve Patient Care.”

The efforts are now maintained by India’s Quality Improvement Board members. Under their leadership, the timelines, structure and processes of the program have undergone continuous refinement, including an improved selection process, virtual breakout sessions, and in-person workshops tied to specific outcomes. These improvements emerged when the quality improvement hub team in India (India-QI-Hub) applied the QI methodology on its own training processes.

“We have learned much from their enhanced QI learning approach, and even made modifications to our own internal training programs based on this learning.” said Mickelsen.

Vallath and her team have now trained more than 30 palliative care and cancer teams across India and their efforts have resulted in more than 10 publications in international and Indian palliative care journals.

Five years later, these units have greatly expanded their capacity to serve an ever-growing number of patients, and the small, volunteer-powered mentorship initiative has developed into a full-fledged program across India’s palliative care and cancer centers. Homi Bhabha, following that first successful year, became a quality improvement training hub. Viswanath and several other alumni have taken on leadership roles within their institution, and have successfully developed QI training hubs that continue to support new projects.

This program really means a lot to me, our team, and our institute,” said Viswanath. “We’ve learned to break down a huge problem into smaller ones, negotiate and navigate our way through it. As Jake says, we’ve learned how to get better at getting better.”

“The ripple effect is stunning,” Vallath said, adding that the impacts could sometimes be felt very personally. She shared a written observation by a colleague, Dr. Priyanka Augustine, about the program’s impact on her team’s ability to ease pain and suffering among their patients — including a friend and student who developed cancer.

Lorenz agreed: “How many programs can you say have created a sustained national impact and resulted in the publication of so many academic papers?” he asked.

Beyond India

“Nandini and her team showed us that with a little time and a fair structure for learning, a small but committed team can build capacity to improve complex healthcare systems in a way we had never before imagined.”

Jake Mickelsen

Building off the success and impact of the collaborative mentorship approach in India, Stanford leaders have developed a series of related international efforts in global palliative care quality improvement, as well as a new program to support quality improvement in other clinical areas. Inspired by the learning approach and results in India, DeNatale and Mickelsen named the Stanford-based international efforts “EQuIP Global.” Supported by the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health, the program teaches quality improvement methods to medical teams practicing in different-level resource environments around the world, in order to empower them to transform local health care delivery. Vallath said she is happy to see the name continue to be used throughout the world.

As an example of this work taking hold in another high-income country, one of the original PAICE mentors and international palliative care leader, Dr. Meera Agar, introduced the program to her home country of Australia two years ago; it is now in its second cohort in partnership with Stanford. They hope to sustain the program through funding from the Australian health care system and national research grants.

A national program is also under development in Ethiopia, where local health care leaders expressed interest in using the model to provide training in quality palliative care following traditional clinical training.

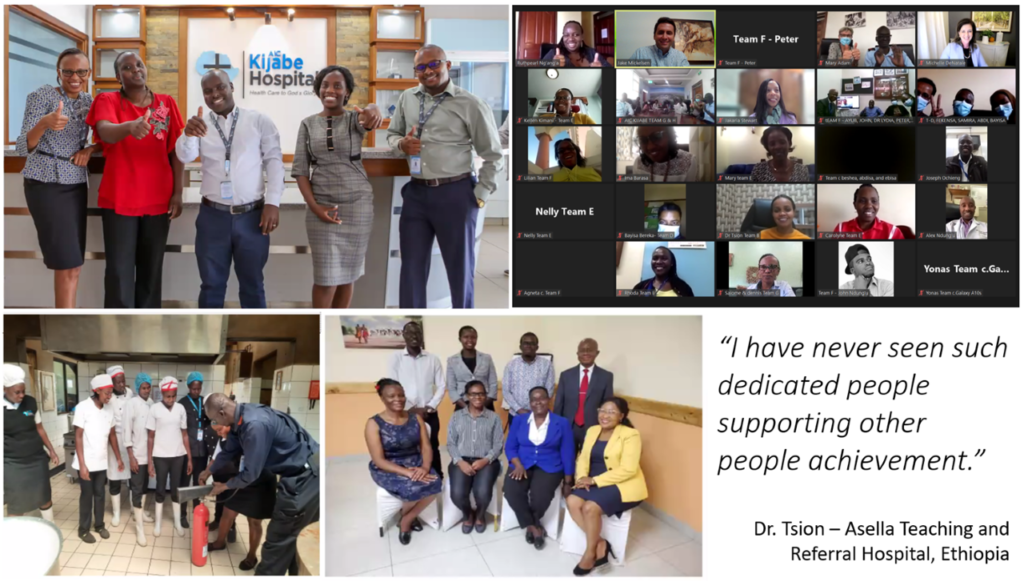

Local clinical leaders in Kenya also learned of India’s successes and reached out with interest to apply quality improvement in their local settings. They have now completed two 6-month cohorts and are working with local non-profits to build structures and systems to support this work.

“I am proud to see our vision of building a network of improvement communities cross the globe and have such sustainable results with engaged membership,” said DeNatale. “This work has fostered new innovations and care models that improve the quality of care delivered with little to no new resources provided. Through this cohort we have engaged leaders and their front-line teams to take their clinical knowledge and daily workflows and be active problem solvers.”

As Global Health Faculty Fellows, Mickelsen and DeNatale hope to secure funding to support the expansion of EQuIP Global, which until now has run almost entirely on volunteer time. Funding could support mentors traveling overseas to work with local clinical teams and even the development of a cloud-based knowledge and data sharing platform to record case studies, measurements, project results, and empower more collaboration.

“We want to work with global partners to grow their own local improvement capability,” Mickelsen said. “Nandini and her team in India showed us that with a little time and a fair structure for learning, a small but committed team can build capacity to improve complex healthcare systems in a way we had never before imagined.”