Published: 05/17/2022

A Stanford Global Health Seed Grant helps kickstart a groundbreaking research partnership between Global Health Faculty Fellow Ami Bhatt and South African researchers to understand the gut microbiome in communities transitioning from rural to urban lifestyles

In 2016, Stanford Researcher Ami S. Bhatt, MD, PhD, met with researchers and fieldworkers from several rural and suburban towns in South Africa to pitch a research project that had the potential to be a tough sell: She and her South African colleagues were there to ask the community members if they could collect and study their poop.

Bhatt, whose lab specializes in studying the diversity of the gut microbiome and its impacts on health, was hoping to conduct an unprecedented pilot study to look at the bacteria in the stomachs of communities transitioning from rural to more urban, and often wealthier lifestyles. These bacteria, she thought, could help understand, predict, and treat new health problems these communities were experiencing as a result of changing diets and ways of life.

While it’s easy to imagine such a request going awry, Bhatt and her collaborators were careful to explain to their collaborators, and later, the residents of the communities they wished to study, how they hoped this research could be of use to them.

As parts of the African continent rapidly develop, people with means are facing a dramatic rise in new health challenges like obesity and heart disease. At the same time, many others still live with food insecurity and malnourishment. A group of African researchers including members of a health and demographic surveillance consortium called INDEPTH had recently launched the H3Africa AWI-Gen Collaborative to study how these changing health trends impact cardiometabolic health. They set up an extensive, meticulous system for surveying and collecting health data on thousands of participants in numerous locations across the African continent.

When Bhatt joined Stanford in 2014 and was introduced to the AWI-Gen effort through the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health (CIGH), she wondered if the microbiome could help shed new light on their work. In 2015, she received a $15,000 Global Health Seed Grant from CIGH to study this question in partnership with Scott Hazelhurst, a professor of electrical and information engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa who was working with the AWI-Gen initiative led by Michèle Ramsay, Director of the Wits’s Sydney Brenner Institute for Molecular Bioscience.

But first, they needed buy-in from the communities they wished to study: Soweto, an urban/suburban township in the Johannesburg area, and Bushbuckridge, a rural, agricultural area in eastern South Africa. Community engagement was built into AWI-Gen’s model, and each community was represented on a volunteer-run advisory council of local residents who considered new research proposals, helped researchers refine them based on local considerations, and decided whether they were appropriate for a given community.

Photo Credit: Ami Bhatt

Most of these volunteer representatives didn’t have scientific training, but, through decades of partnership with the INDEPTH consortium, had gained an appreciation for how research could help their communities improve their health.

So when Bhatt and Hazelhurst made their unusual pitch, community members responded not with distrust or fear, but rather curiosity and interest.

“There was a lot of laughter,” recalled Bhatt, who has served as Director of Oncology for the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health since she came to Stanford. “Some people were like, ‘You’re crazy.’ But once we got over the initial chuckles and explained what we were hoping to do, there was real curiosity and interest to know more about the microbiome and potentially have so many questions answered.”

Residents started asking questions and suggesting topics for the study. “There was just a lot of active engagement in helping us figure out who and what we should study – and why,” Bhatt said.

Thanks to the community’s interest and involvement, Bhatt and her colleagues published in February, 2022, a groundbreaking paper on the gut microbiome of women in communities transitioning from more traditional lifestyles to more westernized ones. Based on its success, they’re now expanding the study to nearly 2,000 women across several African countries to learn more about the gut microbiome and how it affects health. The initiative has also helped shape the careers of several trainees working with the researchers, including that of Ovokeraye Oduaran, a postdoctoral fellow working with Hazelhurst and a key collaborator during the study. In 2020, she was the lead author on a paper about the study and its findings published in BMC Microbiology.

Groundbreaking Discoveries

With support and feedback from the Soweto and Bushbuckridge communities, Bhatt and Hazelhurst’s teams gathered samples from about 200 women and used cutting-edge technology to analyze them alongside a robust dataset on residents’ health history gathered through the INDEPTH consortium. While only a pilot study, it marked one of the largest microbiome sequencing project of adults in Africa to date.

The study found significant differences in the microbiomes of women living in rural Bushbuckridge and those in suburban, densely populated Soweto, where residents have greater access to antibiotics and sugary food and drinks. Microbiomes in Soweto were closer to those of people living in the United States, while those in Bushbuckridge were closer to traditional rural communities around the world. The team also discovered previously unknown bacteria, underscoring the diversity of gut microbiomes in Africa and highlighting the need for further research.

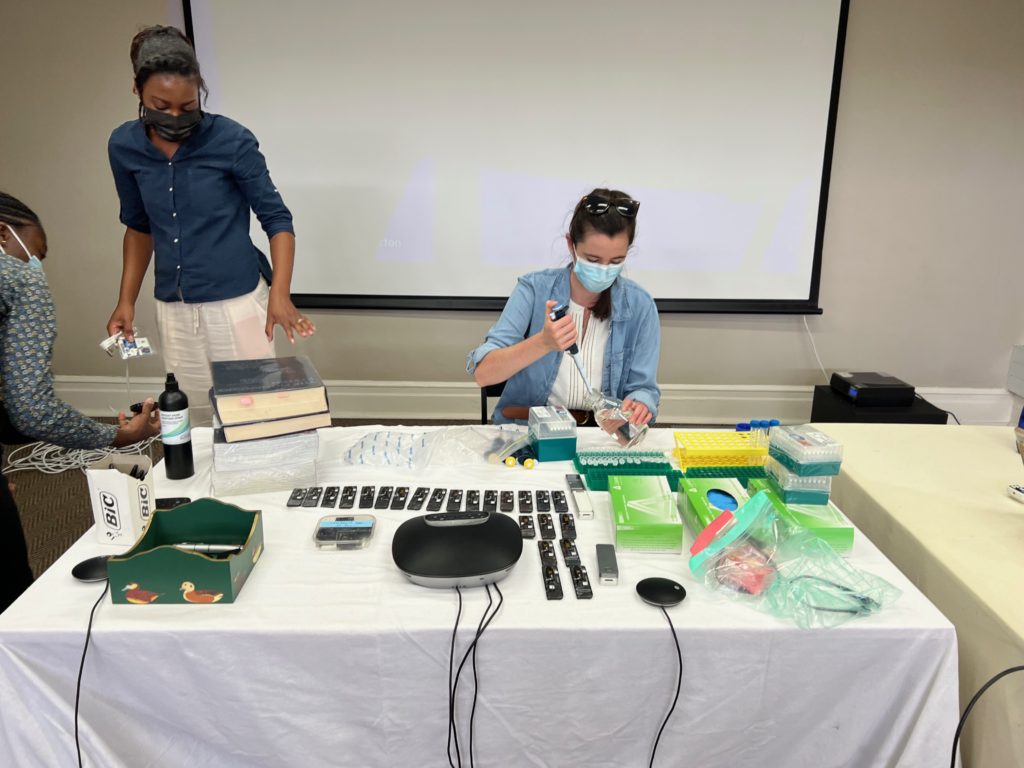

Photo Credit: Scott Hazelhurst

Now, the team is developing a way to share back the findings with the communities that participated in the study — something they see as equally important to publishing an academic paper.

“Our goal is not just to get papers out of this experience, but to try and understand a different community of people, what their needs are, how the resources that we have can be helpful to them — and how the experiences that they have can be educational to us.”

Dr. Ami Bhatt, Global Health Faculty Fellow

“We’re trying to build a long-term relationship with the community,” Bhatt said. “Our goal is not just to get papers out of this experience, but to try and understand a different community of people, what their needs are, how the resources that we have can be helpful to them — and how the experiences that they have can be educational to us.”

In March 2022, Bhatt and graduate student Dylan Maghini traveled to South Africa to discuss with their collaborators the best way to share the results back with participants. They needed an accessible way to deliver the information to many far-flung villages. They settled on a two-page infographic that presents the key findings in culturally relevant, easy to understand ways. They’re now preparing to share the two-page report to participants to get their feedback.

Oduaran said this ongoing communication with local communities is critical to the project’s long-term success.

“The collaboration has worked because Ami and her team come back and engage in a back and forth,” she said. “Because of this, trust has developed.”

“The collaboration has worked because Ami and her team come back and engage in a back and forth. Because of this, trust has developed.”

Ovokeraye Oduaran, Postdoctoral Fellow

From a Small Grant, Big Results

Now, what began as a small project, kickstarted by two modest grants from the Stanford Center for Innovation in Global Health and Wellcome Sanger Institute’s African Partnership for Chronic Disease Research, has sparked a much larger study, helped build African expertise to study the microbiome, and shaped the careers of many young researchers working with Bhatt and Hazelhurst.

Several young researchers have been key to the research efforts, including Fiona Tamburini, who helped Bhatt initiate the project and became lead author on the recently published manuscript; Oduaran, whose postdoctoral work was later funded through a Global Health Equity Scholars grant and who now facilitates a microbiome interest group where individuals across the African continent meet virtually to share ideas; and now Maghini, a PhD candidate and fourth year graduate student in genetics, who joined Bhatt’s lab in 2019.

Photo Credit: Ami Bhatt

Maghini said she initially joined with an intellectual curiosity to apply her computing skills to a “really interesting data set.” Over time, she has become an eloquent advocate for community-engaged research. “It really wasn’t until many months of work and engagement with our collaborators that I started to appreciate the very community-engaged approach and understand the scope and impact this research was having beyond just fun data for us to study here at Stanford,” she said.

The pilot project’s success has now enabled the team to secure funding through AWI-Gen for a much larger sample collection of nearly 1,800 samples from six different sites in South Africa, Kenya, Burkina Faso, and Ghana.

The samples have been collected and transported to Johannesburg, where researchers will help sequence them. Once the DNA sequencing data is generated, researchers from both Africa and North America will collaboratively begin to analyze the terabytes of data that they obtain. Based on interest from local communities, researchers are expanding their study to look at the interplay between the microbiome and cardiometabolic rates, menopause, life conditions, and more.

“The fact that now we’re scaling this up by an order of magnitude and spanning a number of additional countries with very diverse lifestyles and resource access is really, really exciting.”

Dylan Maghini, Stanford PhD Candidate

“The fact that now we’re scaling this up by an order of magnitude and spanning a number of additional countries with very diverse lifestyles and resource access is really, really exciting,” Maghini said.

A Community-Centered Approach

The initiative could never have happened without buy-in and involvement from the Bushbuckridge and Soweto communities, said Hazelhurst.

“From a moral point of view, when working in communities for a long period of time, we’re asking a lot from them,” Hazelhurst added. “It’s important that they are consulted.”

Key to this buy-in was helping participants understand why the information was important – and how it could benefit the health of their friends, families, and neighbors.

“In the neighborhood I live in, if I knocked on your door and said, ‘Would you fill out this tube for me for my study,’ I’d have the door slammed in my face,” laughed Hazelhurst, who lives in Johannesburg.

In contrast to prior AWI-Gen studies, this research would not provide participants immediately useful health information like blood pressure or HIV testing. But, it might offer critical information about the causes of diabetes, obesity, and heart disease — conditions participants were starting to see in their communities.

“From a moral point of view, when working in communities for a long period of time, we’re asking a lot from them. It’s important that they are consulted.”

Scott Hazelhurst, Professor of Electrical and Information Engineering at the University of the Witwatersrand

“There’s a growing understanding that noncommunicable diseases are more common than they used to be and that things like high blood pressure and diabetes pose health problems,” Hazelhurst said.

Community members saw the benefits and offered suggestions. For instance, they said, women would make the best candidates for the study, both due to their availability and their openness to such topics. Some community members shared a possible cultural concern: A common belief that giving something from one’s body to another person makes one vulnerable to witchcraft. To address these concerns, the researchers agreed to destroy the used stool samples.

Photo Credit: Floidy Wafawanaka

Bhatt described this community-engaged approach as one of common courtesy. “If I ever came to your home for dinner, I would thank you for your hospitality and then ask how I could help,” Bhatt said. “Unfortunately, too often, international research doesn’t work like that. It’s more like, “I’m going to come into your home and ask for what I want and then I’m going to leave and use it.”

Beyond being polite, their approach helped them conduct a much more meaningful study, Bhatt said. “We asked such better questions when we came from a position of wishing to be of help.”

Hero Image Caption: A field worker discusses considerations and challenges of field visits and sample collection during a house visit in Agincourt village within the Bushbuckridge municipality.

Photo Credit: Floidy Wafawanaka