Published: 09/01/2020

Dr. Crawford is using COVID-19 as a catalyst for scaling impact in global anesthesiology and critical care, delivering essential trainings around the world, from Rwanda to the Pine Ridge Native American Reservation.

By Anpo Jensen and Lucas Oliver Oswald

For Dr. Ana Crawford, COVID-19 might just be pushing our approach to global health in the right direction. Always troubled with the “service-trip” focus of global health, Crawford has been pursuing a capacity-building approach in her work for years, and the new reality of virtual engagement is now making that approach a necessity.

Dr. Ana Crawford’s training is in anesthesiology, but on top of that she has layered critical care and global health sciences. With this background, she created the Division of Global Anesthesia at Stanford, and has now spent more than a decade working with partners around the world to build out local critical care capacity.

During the pandemic, this global experience has transferred well to a domestic setting in the form of a partnership with the Indian Health Service located on the Pine Ridge Reservation — home to the Oglala Lakota Nation. Years of effective colonization has led to this dramatically under-resourced county being one of the poorest in the country. Health outcomes, likewise, are shocking — the reservation has the lowest life expectancy in the nation. Pine Ridge has faced an uphill battle during the pandemic, but through careful planning and management, the reservation has so far come out on top.

Pine Ridge has had a very effective prevention campaign, successfully keeping community spread to a minimum, but they haven’t stopped there—now they are partnering with Stanford’s Center for Innovation in Global Health to prepare for a potential surge. Crawford, one of our Global Health Faculty Fellows, has led the virtual training efforts with the platform developed for international work, as well as provided guidance for a visiting Stanford Healthcare team.

We sat down with Crawford (virtually!) to talk about how COVID is reshaping her work, and how the principles of global health have applied to this new domestic partnership.

1

How did your career lead to your specific approach to global health?

During my first year of residency, I went on a service trip to Kenya where we ran a four-day health clinic that saw thousands of patients. When it concluded, as my colleagues celebrated, I couldn’t help but recognize that we left the community unchanged. We didn’t contribute to the healthcare system, to clean water education, or to the basic resources the community needed.

That was my introduction to global health; I knew I wanted to do global health and I knew I wanted to do it the right way.

The definition of global health really needs to be reframed. Many people have this antiquated notion that it involves a service-based mission trip where people from higher resource settings come into areas of lower resource settings and basically tell people how they should do things. I feel very strongly that global health is actually public health and that it should start at home.

For anesthesia and critical care, this comes down to health system strengthening and capacity building. Most of our projects are focused on medical education and training.

2

How has your work shifted with the ongoing pandemic?

We’ve spent well over a decade working in medical education and training for anesthesia and critical care, mostly in Africa but also Southeast Asia. Much of this has involved exchange programs and in-person trainings.

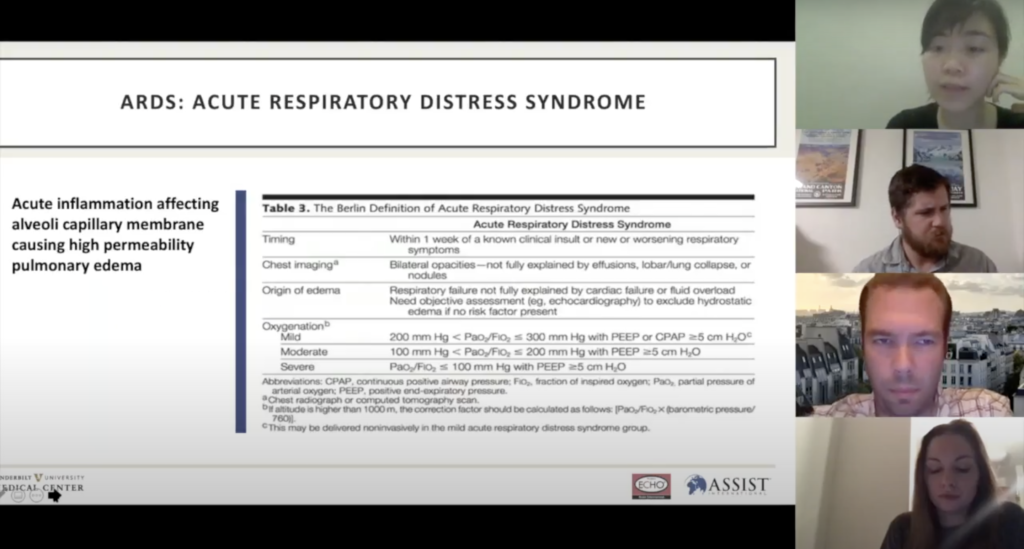

When COVID broke we were in Rwanda working on developing an ICU student manual because there are so few ICU trained providers. When we were forced to leave, we launched the Global Anesthesia and Critical Care Learning Resource Center. We call it “the LRC”. It is an online learning platform with really amazing features.

It’s interactive, with learning modules, courses, and webinar sessions. It also has a community page and a discussion forum, so even when people are not on a webinar and they’re learning independently they can still use those social boards to ask questions and get solutions from colleagues. There’s also interactive quizzes and videos. It’s really quite fun.

Many of the needs have to do with COVID, for instance, supplemental oxygen, the number one treatment or intervention for COVID-19. Surprisingly, oxygen is largely unavailable in many places. So we ran a series on basic oxygen supply with a focus on COVID for Africa and then Southeast Asia. We just agreed to continue for another 12 sessions.

I have been absolutely blown away by the expansion of the global network. We have close to 500 users since we launched in May. This Sunday, I was watching movies with my husband while texting a colleague in Yemen who I’ve never met, helping him through a COVID case. It’s just such a powerful thing to be able to sit in Oakland and help a colleague in Yemen through a difficult case.

3

You have been utilizing the Learning Resource Center in your work on the Pine Ridge Native American Reservation. What has it been like using this resource, largely developed for international use, in a domestic setting?

Like I said, global health should start at home, which is why we are feeling so grateful and privileged to be working with a community that’s a lot closer to home. Safe and equitable access to healthcare is a problem everywhere.

Some background on the Pine Ridge Native American Reservation— they have done an amazing job preventing COVID. It’s a case study in public health — they’ve drastically reduced community spread through basic, scientifically proven public health measures that the rest of the country has failed to implement.

Likewise, they are also being proactive about treatment for if and when it is needed, which is why they reached out to us. The hospital in Pine Ridge is small and none of the staff are trained in critical care. There is no ICU. So, we did a needs assessment and were able to fill some gaps with the LRC. But there were certainly some differences.

The Pine Ridge physicians are US trained. That contrasts with some of our work where we have an audience that includes medical students, nursing students, and nursing providers that probably have a lower level of experience and training. As a teacher, you’re always trying to capture your entire audience so you teach to the lowest and the highest skill level in the room. It’s actually much easier when you know, and can easily assess, the level of knowledge and skill of your audience. They were already very knowledgeable, so in some ways it has been easier to speak at that higher level and narrow in on very specific questions.

4

You were involved in sending a Stanford healthcare team to Pine Ridge to do further capacity building. What did you focus on for that in-person work?

Originally, I was planning on going with the team — two Stanford nurses and a respiratory therapist — but three days before leaving a chronic stress fracture of mine worsened and I couldn’t go. But the team was flexible and still incredibly enthusiastic. So, we made it work.

We started with the needs assessment, which is the beginning of almost every partnership. We imagine the ideal goal, tangible resources, providers, systems, and compare that to the existing situation, then you can start to notice the gaps that need to be strengthened. That assessment includes the four S’s. Space, Stuff, Staff, and Systems.

Many of the resources that would be needed were already procured, PPE for example, a lot of the airway equipment and medications. They even identified a space where a potential temporary ICU could be scaled up. Their biggest need was staff or critical-care trained personnel.

Pine Ridge transfers most of their acutely ill patients out to Rapid City and Sioux City. If there is a COVID surge in Rapid City though, and the hospital there loses further ICU capacity, that has implication for Pine Ridge — they will lose their ability to transfer those patients out. So the team focused on training the Pine Ridge providers that have overlapping skill sets with critical care for these kinds of scenarios.

5

How do you imagine the Learning Resource Center work continuing after the pandemic?

That is a great question! We are not designing this for COVID. This is what we should have been doing all along, especially when building critical care or capacity.

Global health has really interesting chapters: it was highly focused on infectious diseases and then it moved to non-communicable diseases. Now, it’s shifting away from service based and more towards education.

My cohort has been beating the drum for quite some time about perioperative care, safe surgery, and anesthesia because we realize the morbidity and mortality at the hands of low resources and training in those fields. And so, I think that building critical care capacity has still been under represented as a priority in global health.

Many, many years ago, I told people I wanted to do ICU and global health and I had people laugh. I had a faculty mentor say, “That doesn’t exist.” But in my mind, it’s always existed and needs a lot of help.

Critical care is a necessity; it needs to be built up and it happens regardless if you have an ICU. It happens everywhere. Whether you have an ICU or not, you still have to provide care that is critical to your patients. Just like global health, critical care needs to be reframed. I’m working to make providers realize what they can do even if they don’t have an ICU.