Published: 01/01/2016

A global health blog from Stanford medical student Luqman Hodgkinson, PhD, on progress in research and medical education in his hometown of Kakamega, Kenya

Week 10: Peaceful Endings

Dr. James Bill Ouda presents me with the research license from the National Commission of Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Kenya.

23 Aug 2015 – This week it was my pleasure to bring our project to a close in preparation for my return journey back to Stanford. Working up to the last hours, we obtained complete data for 306 patients, complete within the approvals we received. It was my great pleasure and privilege on Saturday to receive consent from the 306th and final participant eligible within our approvals.

The Directorate of Research and Extension (R&E) at MMUST was very helpful to our project. In particular, James Bill Ouda, PhD, Research and Extension Assistant, worked very hard to make the project a success. Dr. Ouda traveled personally to Nairobi to obtain the hard copy of our research license from the National Commission of Science, Technology and Innovation, Republic of Kenya, and deliver to us before my departure. Letters of authorization were also received from the County Commissioner and the County Director of Education for the county of Kakamega.

With every close to a journey there is an element of sadness. Joy to have completed the research project to perfection beyond initial expectations, but sadness to leave my home country of Kenya. It remains a simple pleasure to ride my bicycle on paths traveled by young tender feet of mine when I was four years of age in 1984 and on my bicycle throughout my childhood up to 1998 when I traveled to America. When I return to Kakamega, I am truly at home.

My heart always yearns to be with my family and my children. Throughout this entire journey I have stayed with my foster parents who cared for me and protected me from the time I was ten years of age until now. Every day when I returned home from work on my bicycle, my favorite foods would be waiting for me, and my children would be ready to join with me to partake in our simple supper. It is my great pleasure and privilege to express my appreciation to my family for their immense contributions to my life and to my research.

My children are the most important reason for my research. In 2005, the AIDS pandemic left them as orphans. My foster parents who were retired from work persevered very hard to raise their grandchildren, but with challenges of their own it was a heavy burden. When I saw my foster father in 2005 I feared for his life from the stress and the burden. Realizing it was necessary to lighten his load, I took the five children to be my own, and since then they have been the sunshine in my life.

A new chapter has opened in the story of the AIDS pandemic. No longer is HIV a death sentence. Medications are widely available in Kenya and distributed free of charge to eligible patients. With good adherence to antiretroviral medications, life expectancies can be quite long, and parents remain to live to care for their children. Even children who are born with the virus can live to see adulthood and continue in life with a good prognosis. The darkest days are behind us and a bright future awaits.

Week 9: Expressions of Gratitude

16 Aug 2015 – Not everyone has the privilege to acquire sufficient knowledge to give back to their community. In my case I have been very fortunate.

This was a busy week consenting patients and obtaining data from the medical records. Each patient who arrives for consenting also receives counseling from the medical staff. Expressions of gratitude from patients for their treatments are many. One week remains and we have obtained complete data for 253 patients from the 330 patients who receive antiretroviral medications from Emusanda. A significant number of patients are not eligible for our study as they may be younger than 18 years of age, they may be pregnant, they may have history of mental illness, or they may be temporarily transferred due to travels; our approvals are very specific. We imagine that we may be able to record data from 280 or 290 patients by the end of our study, which would be complete for the approvals we have received.

This week it was a great pleasure and privilege to meet with all 10 community health workers who are so important to the community, who assist patients to live lives of hope, and who work to ensure that patients remain faithful to their medications. The community health workers have been essential to our study as they’ve help bring patients with challenges to reach the health centre for the consenting process and their medications. Because of the gentle approach of the community health workers, not a single patient has yet refused to participate in our study.

Carolyne Tsisiche, one of the medical staff at Emusanda, has devoted full-time effort to ensure that we would obtain sufficient data for a complete study. It has been a great pleasure working with her, with Clinician Makori, and with Educator Okwiri to perform this important analysis of patients’ adherence to antiretroviral drugs in Kakamega.

Donating Mandell, Douglas, and Bennett’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, Eighth Edition, 2015, to Educator Okwiri, Educator Tsisiche, and Clinician Makori for use at Emusanda.

Current knowledge is essential for improving treatment. At a facility where Internet connectivity can be a challenge and resources for the latest knowledge are limited, many treatments rely mainly on experience and intuition. As a medical student, I arrived at Emusanda fully equipped with textbooks and materials. One reference text in particular, Mandell, Douglas, and Bennetts’s Principles and Practice of Infectious Diseases, Eighth Edition, 2015, caught the attention of the medical staff and they began to use the information in the text to enhance their treatment of patients. Not a cheap text, having been purchased on Amazon for $465.73, it had not been my initial intention to part with the text at this time. Yet, as I began to see the extent to which patients benefited from latest knowledge, it became my great pleasure and privilege to donate the text to Emusanda for their use in treating patients.

It is my hope that readers of this blog begin to understand the extent to which patients appreciate the treatments they receive through Emusanda, the extent to which the medical staff appreciate relationships with the outside world, and the extent to which I continue to appreciate the opportunity to work with the medical staff to contribute to our community. It has truly been a great pleasure and privilege and one week remains.

Week 8: Room for Expansion

10 August 2015 – It was my pleasure this week to conduct an interview with the chairman of Emusanda Health Centre, Stanley Ingoka. Though Chairman Ingoka is fluent in English, the interview was conducted in Kiswahili, mainly because Kiswahili is my preferred language and it seemed natural to maintain our usual conversation. Highlights of the interview have been faithfully translated.

Chairman Ingoka shows us the land available for patient wards and a maternity wing.

Dr. Hodgkinson: Can you provide us with a brief history of Emusanda Health Centre?

Chairman Ingoka: Some time ago the Government of Kenya built the basic structures under the Constituency Development Fund (CDF) but they lay dormant for some time and were not equipped. Later on the government of Kenya, together with the company of Vestergaard, began a campaign to test people for HIV/AIDS and Emusanda was one of the stations used for testing. Many people came to be tested at Emusanda and it was clear that the demand for treatment was high. The community communicated with donors including Mikkel Frandsen of Vestergaard and Yvonne Chaka Chaka who brought the government on board. At present the health centre is supported in part by Vestergaard and in part by the government of Kenya. The services are many and good and people come from far to be treated here.

Dr. Hodgkinson: What are some challenges the health centre faces?

Chairman Ingoka: The biggest challenge is lack of funds. Services here are equivalent to the level of a health centre, but there are no patient wards or maternity wing so it is registered with the government of Kenya as a dispensary. There is enough land to build a maternity wing and patient wards but the money to build these is not enough. At present many people who come to be treated here must be referred to be treated elsewhere because there is no ward with patient beds and no maternity wing. Many women give birth here at Emusanda but there is only a small room that we use for this and it is hard to help the women give birth. So there are challenges and any well-wishers that can help with this are very welcomed. If we could have these facilities the hospital would be upgraded to a health centre. At present our staff are often transferred to other facilities because we continue to be registered as a dispensary. If we could be upgraded to a health centre, our staff would not be sent to other facilities and the government would add us even more staff. Patient wards and a maternity wing would allow people to receive better services.

Dr. Hodgkinson: Stanford University greatly emphasizes research and conducts research throughout the world. My own research is being supervised by Dean Michele Barry, senior associate dean for global health, who coordinates research projects globally. Chairman Ingoka, what are your thoughts on our research and your vision for Emusanda with regard to research?

Chairman Ingoka: In our community a major problem we face is malaria. Malaria prevalence has really gone up. If you look at our records you will see that treatment of malaria has really gone up. We would like to have some research on this. When so many people are contracting malaria this is affecting our economy adversely as many people are being taken to hospital and it costs large sums of money to treat them, which is creating poverty for our people. So if we are able to conduct research to see what is causing so many people to be getting malaria in this area it would be very good. In addition to malaria we are also finding that the sickness of high blood pressure is really troubling people. When people are getting this problem of high blood pressure, their health becomes poor and they become very weak and it is hard to continue their lives in a good way. It would be good to have some research to know why it is. Another problem that troubles us very much in this area is that we have our brothers and sisters with HIV and AIDS. It is good to have research on how to use their drugs well and to get food that will help them and to be guided and counseled to live lives of hope. These are just some of the topics that we in this area would like to join in research with any organization. We were discussing with our brother Luqman that our brothers and sisters at Stanford may see the benefit to come to work with us and maybe even help us to become a research centre in this area so that our people can have sufficient research, prevalence of various illnesses can be decreased, and people can continue in a good state of health.

Dr. Hodgkinson: Our research is conducted jointly with Stanford University School of Medicine, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology, and Emusanda Health Centre. What are your thoughts on the relationship between these institutions?

Chairman Ingoka: We have a very good relationship with Masinde Muliro University. Many of our youths go there to study to get diplomas and degrees. So we see that if a research centre can be established here at Emusanda it will greatly strengthen the relationship between our three institutions and our people would continue to study matters of medicine and to know the problems that are troubling our people. So we the community of Emusanda welcome Stanford and MMUST to come closer to us and to work together with us on matters of research.

Week 7: Understanding Health Dynamics

Clinician Makori demonstrates the machine for measuring CD4 counts at Emusanda.

03 August 2015 – Much of the excitement of research arises from the uncertainty of the outcome. Research leads to greater deeper understanding and this understanding guides health services and policy.

The first aim of our research is to identify characteristics of patients who have difficulties adhering to antiretroviral medications. Characteristics that we plan to consider are age, gender, marital status, approximate number of children, approximate distance of home from health centre, food security, date of confirmation of positive status, history of antiretroviral medications, history of co-medications, history of tuberculosis, history of opportunistic infections, and CD4 counts.

Emusanda Health Centre regularly measures CD4 counts although reagents are limited. Most patients receive CD4 counts every two to three years, which is longer than the AIDS.gov recommendation of three to twelve months. Resistance testing of virus mutations is not yet possible.

Additional aims of our research are to examine whether attendance at monthly support group meetings improves adherence to antiretroviral medications and to analyze effectiveness of various forms of contact used by the health centre when patients miss appointments: phone calls, sending trained community health workers to patient homes, and sending fellow patients to patient homes.

Until last week research was moving a bit slowly. A consenting process for each patient was mandated by the Institutional Ethics Review Committee at MMUST to conform with Kenyan law and was subsequently approved by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. The consenting process is consuming considerable time. Consent is then followed by a lengthy process to obtain each patient’s medical records. The medical staff at Emusanda Health Centre is very busy treating patients so the consenting process and recording of medical records were progressing more slowly than I had anticipated. After I discussed these concerns personally with my supervisor, John Arudo, RN, MPH, MSc (Clin. Epi), Chairman of the Department of Clinical Nursing and Health Informatics at MMUST, Chairman Arudo drove personally to Emusanda to ensure that a member of the medical staff could devote full-time work to our project for the next three weeks. At present the research is progressing at a nice rate.

Slightly more than 300 patients receive antiretroviral therapy from Emusanda Health Centre. At present we have obtained records for 126 patients. It seems possible at the present rate that within the next three weeks we could exceed 200 records.

Week 6: Ambassador Checks In

27 July 2015 – Research has been progressing for several weeks. On weekends I stop at the MMUST library to write the blog entry for the week and to send emails. Internet connection is a particular challenge in other locations.

The vice chancellor of MMUST is a busy individual with a position equivalent to president of the university. This week we were able to set an appointment to see him.

He was happy to see us. The medical school has been his personal project for some time. He wishes to begin “a strong medical school that can be a blessing to the two million people of Kakamega” at which people can receive quality medical care and training. He envisions it being a centre for “research and innovation” and “proactive preventative health.” Referring to a broad spectrum of illnesses, including both infectious and non-infectious diseases, he said it is “hard to cure these ailments once they set in.”

He was happy to see the blog and to know that they are “not isolated.” He said that the medical profession in Kenya has not done “as much research as should be done” and that it was a “major breath of fresh air [for us] to come in to understand the health dynamics.” He explained that much research is needed to “work with the hospital to cut down on medical bills.”

Meeting with MMUST vice chancellor Fredrick Otieno.

He envisions a “departure from the traditional way of training doctors.” He notes that “computer simulations help more and more without incurring high costs” and hopes to see “Stanford support in the medical undergraduate programs.”

He said he was “keen to sign a formal MOU [Memorandum of Understanding] if Stanford finds it appropriate in the coming months to become partners in Kenya and East Africa.” He would like to see students and faculty “moving from here to there and there to here.”

Vice Chancellor Fredrick Otieno thanked us for our work and remarked that he understood the sacrifice for an individual with a PhD to return to medical school.

Speaking to me directly, he said, “thank you to humble yourself to do what you have done, to return to medical school and to tap into humbleness and the spirit of giving. We encourage you to continue to serve as a good ambassador and to be a role model to young men and women in the county of Kakamega and the country of Kenya. We will give you as much support as we can to make your role as ambassador and role model as effective as it can be.”

Week 5: Supporting One Another

19 July 2015 – HIV is a virus that crosses boundaries. People of all backgrounds suffer from it though they may share very little in other regards. Each person may feel very alone. Sometimes the virus is a secret not shared with many, perhaps no one.

Educator Okwiri finds himself the leader of a diverse group of people striving for hope, for comfort, for companionship, and—often—basic sustenance. Some travel long distances to Emusanda to ensure that their status is not discovered by those living near their homes. Others find even short distance travel by vehicle or motorcycle to pose financial challenges and they travel more than ten kilometres by foot to obtain drugs.

How to organize this diverse group of individuals to provide meaningful support challenges even Okwiri. Examining the records of the support group at Emusanda I see many changes, many good ideas, many failed projects. There was once a project with chickens that died in due course. Meetings were held twice per month, sometimes only once.

Okwiri notes three groups of people: those with resources, those with little, and those in deep poverty, with most PLWHAs in the latter category. PLWHA is an acronym for People Living With HIV/AIDS and is pronounced “plu-wah.” Those with resources often join support groups, if at all, only for moral support. Those with little are very interested in mutually supportive projects. Those in deep poverty are also interested in mutually supportive projects but have nothing to give.

This diversity has led Okwiri and others to organize two tiers of support groups. The first tier, which meets once per month, is for moral support and education. Sometimes the meeting dates change and it can be difficult for some members to know when it is meeting. Perhaps three times per year visitors come to speak from Kenya Red Cross Society, African Medical Research Foundation, or Afya Plus, the latter a distributor of antiretrovirals from PEPFAR. Educational support group events are sponsored by the Global Fund.

The second tier of support group is for those members who wish to engage in agricultural projects for self-improvement. They meet once per month and maintain detailed records including of attendance. The membership dues deter some people from joining, but Okwiri and others make efforts to ensure that everyone is welcome to participate regardless of their ability to pay.

Of late, they have been raising goats and sheep after support group members pooled funds. In total they have purchased seven goats or sheep. Goat milk is good for their health and they hope that when the goats give birth, each member can receive one or more. Yet there are challenges. Three female goats remain with Okwiri. Of the four animals distributed to members, only two remain as two were sold by members due to family emergencies. This bothers Okwiri as the condition of receiving a goat was that the member needed to ensure it gave birth and to return a baby goat to the group.

Yet organizer Okwiri does not give up. A new idea is that if they can obtain a male goat they can birth a number of goats in the main group. Members would place their names on a rotating list. As goats gave birth each member would receive a goat without conditions to manage as they pleased. The ideas are good but funding is a constant problem.

Week 4: Drugs, Not Enough Food

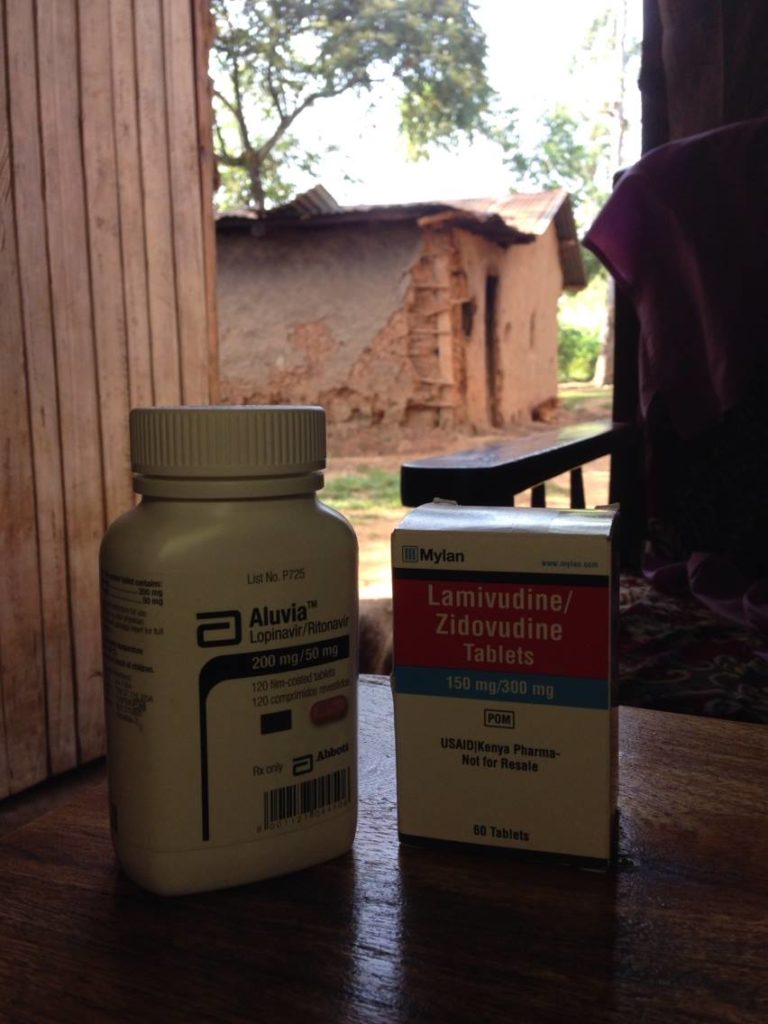

Typical antiretroviral drugs in a local home.

11 July 2015 – A panoply of antiretroviral drugs: zidovudine, lamivudine, nevirapine, efavirenz, lopinavir, ritonavir, and others. “Lamivudine is always used,” says Mr. Okwiri, often in combination with zidovudine and efavirenz. Sometimes nevirapine is substituted for efavirenz and some people receive tenofovir rather than zidovudine. Decisions are often made by availability of drugs and sometimes patients are advised to persevere through painfully troubling side effects.

Headache, malaise, fatigue, dizziness, vomiting, itching, racing heart, and restless nights are but some of the side effects that patients might experience. Since I arrived less than one month ago, more than 100 patients with AIDS have been seen at the Emusanda Health Centre. Listening to their stories has taught me much about human strength and perseverance, and the importance of food.

“Try your best to eat a balanced diet,” says Mr. Okwiri in Kiswahili to the patients. But in private he tells me, “it is not possible for most people to eat a balanced diet.” For a lesson in poverty I recommend visiting those suffering from AIDS in rural Kenya, some of the most destitute of people.

This is often how the story goes: The virus arrives, but no one knows how. A husband or wife dies, the children are born with it. Long illnesses. Someone is tested. A partner discovers it and abandons his or her spouse and family. Families are broken, children suffer.

In the 1990s in Kenya, many people with HIV did not have access to antiretroviral treatments and died. Orphanages sprouted. By the early 2000s, I remember speeches from US Congress asserting that allowing generic antiretroviral drugs in “the developing world” would not allow sufficient profit for drug companies. Millions more died for this greed. Then came PEPFAR, and with it came drugs.

People are grateful for the medications, despite that many of them are essentially starving, without food to supplement their treatment. “What if we have no food? Should we still take the drugs?” Time and time again, Mr. Okwiri responds simply, “yes”.

The drugs are harsh as I know from personal experience just having taken the antiretroviral, post-exposure prophylaxis. It is very important to have sufficient food when taking these drugs. But with frequent destitution caused by deaths and abandonment, often compounded by stigmatization of those with HIV, the only way for many people to eat is through hard labour digging in the fields.

“Kibarua” is the name for this daily labor. It requires searching for a field to dig or neighbors’ clothes to wash and hoping that the owner of the field or recipient of the labour has enough to give for a rudimentary evening supper. Most cannot find “kibarua” every day and so they sleep hungry. For a mother, “kibarua” often provides just enough food for the children and she sleeps on an empty stomach filled only with antiretrovirals.

Some patients abandon hope and stop taking their drugs regularly. Many claim that antiretrovirals diminish their ability to carry out hard labour and that side effects are intolerable without food. When I see the most extreme cases of patients suffering and listen to their plights, I am reminded of the complex challenges these individuals and communities face. The drugs are available, but food is not.

Week 3: Open Doors

Kakamega Health Minister Peninah Mukabane in front of a map of health-related facilities in Kakamega County.

4 July 2015 – On Monday morning, Chairman Sakwa and I met with the Minister for Health for Kakamega County. Minister Peninah Lung’adzo Mukabane is a member of the cabinet of the governor and promptly welcomed us with a round of chai. On the wall behind her desk hung a map of Kakamega County, colour coded by constituency, with names of all health-related facilities in the county, whether private or public.

The session was sobering as Minister Mukabane explained to us the unmet health needs in this county of two million people – only 12 physician specialists exist in the entire county, including one anesthesiologist and one radiologist, and the vast majority of residents do not receive advanced specialist care. She warmly welcomed any and all collaborations to improve the health of the county and promised any support we need.

Our next stop was Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) to meet with Dr. Charles Maringo, dean of the School of Medicine. An active man who studied medicine at the University of Nairobi and at Johns Hopkins in Maryland, Dean Maringo explained to us the great progress they have made since receiving authorization to begin the medical school in January. He takes great pleasure in being an agent of change to ensure the success of the school of medicine.

Having been born and raised in Kakamega, Dean Maringo’s heart belongs to the people and the country. As he walked with us around the MMUST campus, he raised his hand and waved to the hills behind the university saying, “You can see the forest from here.” He believes the forest contains assets for the health of the people including undiscovered medicines from natural sources, a resource that has not yet been fully investigated.

Dean Maringo walked with us through the laboratories and facilities. Given their mission to be a university of science and technology, MMUST strives to bring technologies to their facilities. It is through technology, Dean Maringo believes, that the unmet health needs of the county will be met. The entering class of medical students in September, hoped to be 40 in number, carry the hopes and dreams of the county to treat the untreated, and to reduce the burden of illness for residents of Kakamega.

Dean Maringo described his vision for the school of medicine eloquently. Harnessing the MMUST mission to foster technological innovations, he dreams of being a centre for medical simulations to enhance medical education, ranging from mannequins for student education to surgical simulations for continuing medical education.

“In a county with limited number of specialists,” he told us, “doctors must know how to do everything.”

Developing simulation software and facilities, he believes, will increase the skills of medical students and physicians and decrease risk to patients. Dean Maringo warmly welcomes collaborations with Stanford University and wishes to share a direct quote:

“Belonging to a science and technology university, the School of Medicine of Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) is well positioned to embrace new technologies, thinking and training in the provision of quality medical care. In this regard, the school is looking forward to developing high-end medical, surgical and diagnostic simulation laboratories to support student skills development, competencies, and confidence in patient care and to enhance patient safety. We therefore and whole-heartedly welcome medical collaborations in research, medical education and technology innovations.”

“The recent visit to MMUST by our adjunct associate researcher Dr. Luqman Hodgkinson is welcomed, is encouraged and it truly fosters further collaborations/partnerships. I look forward to further visits by faculty and students from Stanford University. I am particularly interested in the area of medical innovative technologies and their applications in training and service delivery.”

Week 2: Arriving at Emusanda Health Centre

26 June 2015 – A busy and exciting ten days have passed. Waiting to collect me in Kisumu International Airport last Thursday was Josphat Sakwa, Chairman of Kakamega County Council of Elders, a committee of 100 elders who advise the governor on all political matters. Chairman Sakwa has been instrumental in advancing the relationship between Masinde Muliro and Stanford, and has known me from the time I was a child of four years of age when he was chief of a large region in Kakamega.

It is hard to find a location more distant from Stanford than Kakamega. At ten hours time difference, we are nearly halfway across the globe. Such a time difference can be a challenge to adjust and it was nice to be at home with family and friends.

Signing official form of faculty appointment at MMUST with Dr. Elizabeth Abenga and Chairman Sakwa.

Early Monday morning Chairman Sakwa and I arrived at MMUST to meet with Dr. Elizabeth Abenga, director of international relations and academic linkages, and with Dr. John Shiundu, professor of education. Dr. Abenga presented me with original documents of my faculty appointment to sign in her presence. We were presented a letter from the chief officer of health services of Kakamega County offering all necessary support for our research collaboration. Meetings with the vice chancellor of the university and the dean of the medical school are being arranged.

Soon after, I began volunteer work at Emusanda Health Centre assisting clinician Jorcelyne Makori and her medical staff to care for the many patients who reach the health centre from a large catchment area. Patients arrive with all maladies ranging from malaria, typhoid, and intestinal worms to infected wounds, family planning injections, RTIs, UTIs, and complications from AIDS. The medical staff see patients non-stop from morning until late afternoon and were very happy to receive my assistance as volunteer. It is clear that Clinician Makori finds great pleasure in providing instruction on treatment protocols and available medications.

Peer educator James Okwiri is a brave individual with HIV who has been publicly open about his HIV status and serves as a role model to others (click here for his story). Educator Okwiri met with me to discuss our plans for the research.

Eleven community health workers are affiliated with Emusanda Health Centre and each serves patients from a different region. Together we arranged a coordinated effort to bring 300 patients receiving antiretroviral medications to the health centre to begin the participant consenting process for our research. The research aims to advance our understanding of the effectiveness of community outreach programs for empowering individuals to maintain optimal adherence to antiretroviral regimens. Clinician Makori expressed happiness with this effort for yet another reason: the consenting process itself may assist medical staff in encouraging patients to come to the health centre for treatment. It is an exciting time as we see this coordinated effort beginning.

Week 1: Bright Beginnings

16 June 2015 – Exciting new developments are taking place in Kakamega County, a rural county in western Kenya, and members of the Stanford community have a unique opportunity to be part of this adventure.

By population, Kakamega is the second largest county in Kenya, behind only Nairobi, having nearly two million people. Yet for many years, Kakamega did not have a medical school. In January 2015, Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST), a leading university in Kakamega, received authorization to begin the very first medical school in the county (full story here).

In the days before these exciting developments, when medical technologies and services were even more limited than they are today, I was a child in Kakamega. Now a first-year medical student at Stanford University, having entered with a PhD in computational biology from the University of California, Berkeley, it was my great pleasure to receive a faculty appointment as adjunct associate researcher at the new MMUST School of Medicine in my hometown and to be designated ambassador from MMUST to Stanford.

Medical research of all kinds is greatly needed in Kakamega to advance the health of the community, particularly in the area of HIV. In Kakamega County, the HIV prevalence is 5.6 percent. Addressing the local HIV pandemic is what inspired me many years ago to pursue medicine and now for the first time I am on my way to join this endeavor.

With the help of Michele Barry, MD, FACP, senior associate dean for global health at Stanford University, we designed our first research project to study community outreach programs at Emusanda Health Centre (a satellite facility of MMUST School of Medicine) with the goal of empowering optimal adherence to antiretroviral medications among community members with HIV/AIDS. We plan to evaluate the efficacy of these programs and the demographic factors that may impact adherence.

This first blog entry finds me on an airplane to Kakamega where I will remain through the end of August collecting data and building the foundation for our research. Through a series of blog posts, I will share updates on our progress and chronicle collaborative opportunities available to members of the Stanford community with the new MMUST School of Medicine. Relationships are very important in medicine and this is also true for a medical school that is at the beginning of a bright future.

Luqman Hodgkinson, PhD, is a first-year medical student at Stanford University School of Medicine from Kakamega, Kenya. This summer, Hodgkinson is returning to Kakamega as an adjunct associate researcher at the new Masinde Muliro University of Science and Technology (MMUST) School of Medicine – the first medical school in Kakamega County – expected to open later this year. His first research project in Kakamega focuses on the efficacy of community outreach programs designed to improve adherence to antiretroviral medications among adults with HIV/AIDS.

Through a series of blog entries, Hodgkinson will chronicle his experiences in Kakamega and share opportunities to get involved at this exciting time for the MMUST School of Medicine. Follow along!

Hodgkinson is the ambassador to Stanford University from MMUST School of Medicine and can be reached at luqman@stanford.edu.