Published: 03/09/2023

Interview by Jamie Hansen, Communications Manager

Dr. Ana Crawford, MD, is on a mission to advance health equity, improve healthcare for patients around the world, and build global community. In 2011, her passion for equitable medical education led her to found the Division of Global Health Equity within Stanford’s Department of Anesthesiology, Perioperative and Pain Medicine.

Since then, she and her colleagues have built one of the first Global Health Fellowship programs in the nation for anesthesiologists, developed a global health pathway for anesthesia residents with overseas rotations, and launched a visiting scholars program that hosts junior faculty from low-and-middle-income countries.

She’s passionate about building bidirectional partnerships between Stanford and overseas partners. During the pandemic, she leveraged these partnerships to provide much-needed training and resources around critical care. She developed the Global Anesthesia and Critical Care Learning Resource Center, which has provided free, online, open-access healthcare resources to more than 8,000 learners in over 145 countries.

Recently, she joined CIGH’s core leadership team, where she shares her expertise in anesthesiology and critical care. This year, she also stepped into a new role as Director of Global Engagement Strategy for the Stanford Department of Anesthesiology. We spoke with Dr. Crawford about her new position and the power of global engagement to improve physician well-being, improve healthcare systems, and cultivate health equity.

What is Global Engagement, and why does it matter?

With global engagement, we take several steps back from our programmatic activities and think, how do we want to define our community? Who do we call our neighbors? Stanford Medicine has a culture of service. So if we want to serve our neighbors, how do we want to define that — locally, nationally, or globally? In my mind, it’s obviously a global community.

In this definition, the educational and service programs we typically associate with global health are included, but there’s also so much more that falls under this umbrella. Global Engagement includes advocacy, physician well-being, being globally informed, cultivating a global community, and appreciating the diversity of patients and colleagues. And ultimately, it’s all about using these tools to improve patient outcomes.

How can physicians and departments benefit from a globally engaged approach?

There are many benefits. For example, professional development: To advance in their careers, Stanford faculty need to develop professionally through publications, committee appointments, and involvement at the local, national, and international levels. Similarly, professional development opportunities are so often missing for our colleagues in low-resource settings. Global engagement opens opportunities for professional development locally and overseas. Some of the most rewarding parts of my job are helping my overseas colleagues get published, engage in research, and conduct quality improvement projects.

Another key benefit is physician well-being. Emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, loss of meaning, and feelings of ineffectiveness all drive the high rates of physician burnout we’re seeing. Providing more opportunities for community-building and community engagement through global engagement can alleviate that. I love my global community; it gives me some of the most joy in my career. If we can harvest opportunities in global engagement that help people feel like they’re part of a community and where they have a chance to help others, that’s wonderful.

What experiences shaped your interest in global health and health equity?

I first got into medicine because I was intrigued by the science and wonder of how the human body works. My future interest in global health wasn’t immediately clear to me.

Then, when I was a preliminary medicine intern, I had an opportunity to travel to a small village in Kenya. I didn’t realize at first that the trip was a religious medical mission. We ran a clinic for four days and saw over a thousand patients. We couldn’t see everyone, and as I watched the missionaries choose who would be seen and who wouldn’t on the final day, the power differential was really obvious to me.

I left feeling we hadn’t accomplished anything. The kids still weren’t in school. There was no running water. There was no sustainable healthcare intervention. I walked away feeling a sense of shame and disappointment, but I also had a clear sense that I wanted to be engaged with global health. And I knew there was a better way.

I put global health on hold and finished my anesthesia and critical care training. I joined the Stanford Department of Anesthesia and decided to pursue a master’s degree in Global Health Sciences from UCSF in 2011. I wanted to be deliberate and understand what I didn’t know about global health. My department chair, Ron Pearl, really supported me as I pursued the master’s and allowed me to follow my vision and build global health programs.

How can a global engagement lens help further the work of the Division of Global Health Equity?

First, I want to acknowledge two people who have helped shape my approach. Dr. Tom Weiser, Director of Global Engagement for Stanford Surgery, provided great mentorship and insight into global engagement. Program Manager Michelle Arteaga has helped me build and shape the Division of Global Health Equity since its early days.

With their help, I expanded my definition of Global Engagement to help focus our efforts around the ultimate goal of building community and improving healthcare systems.

It’s easy to get motivated by competition with other programs or demand from residents, fellows, or faculty for overseas opportunities, but we need to really be thoughtful about why we’re building these programs. Is it to provide opportunities to our residents and fellows? I don’t think that’s the true motivation. That’s a nice side effect. The true motivation is improving healthcare systems and patient outcomes in our partner countries.

Everyone comes with knowledge of their culture, religion, and all these other great attributes that can inform the rest of us when we’re caring for our increasingly diverse patient populations.

Ana Crawford, MD

Global Engagement also offers an opportunity to highlight and celebrate diversity. The anesthesia department has more than 300 faculty; we have all these amazing faculty, trainees, and staff from all over the globe. I want to highlight and celebrate how globally diverse we are. Not only can we recognize the uniqueness of the individuals in the department, but also the valuable resources they bring. Everyone comes with knowledge of their culture, religion, and all these other great attributes that can inform the rest of us when we’re caring for our increasingly diverse patient populations.

What program are you most excited to grow in the coming months and years?

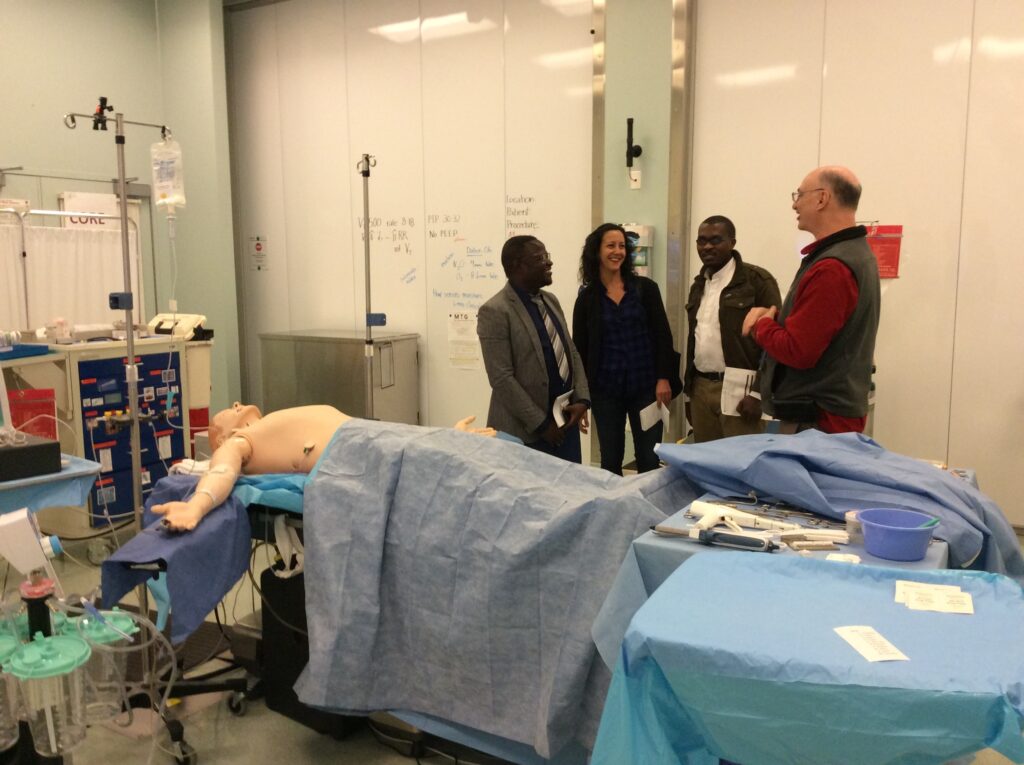

I’m working toward increased grant funding to support our division’s activities — especially the observerships we offer to overseas colleagues. Over the years, this initiative, the Visiting Scholars program, has grown. We now invite junior faculty from our four partner sites in Rwanda, Tanzania, Vietnam, and Zimbabwe to rotate at Stanford for a few weeks, in addition to attending a national meeting of anesthesiologists.

While COVID-19 has created opportunities for robust online training, these observerships offer learning opportunities that are only available in person. Visiting scholars can learn a new skill — for instance, processes for safely taking someone off a ventilator — AND the quality improvement methodology to put it into practice in their hospital setting when they return home.

It’s the program I’m proudest of, and I’d love to grow it into a really robust, bidirectional academic exchange.

Cover photo caption: Dr. Crawford reunites with colleagues for the first time since the pandemic started at the All Africa Anesthesia Congress in Kigali, Rwanda September 2022